The Gay Lens: Frances Benjamin Johnston and Pops Whitesell

One the world's early photojournalists chose to close out her extraordinary 70-year career in the French Quarter, in the company of bohemian artists like local photographer Joseph Woodson “Pops” Whitesell.

- by Frank Perez

The year is 1946. An 82-year-old woman and a real estate agent stand in front of a home on Bourbon Street. The antebellum sidehall American townhouse features a wrought-iron balcony, a neglected courtyard littered with junk, and a former slave quarters building with no electricity. The architectural details are important to the woman. Unbenknownst to the agent, she is the founder of the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South.

His asking price is right — a steal at $4,600. She signs the papers immediately.

The agent perhaps thought the woman was retiring. And technically she was, but she had no intention of slowing down. At the top of her to-do list was the compiling a book of photographs on the architecture of colonial Georgia, and the cataloging of her donation of photographs to the Library of Congress.

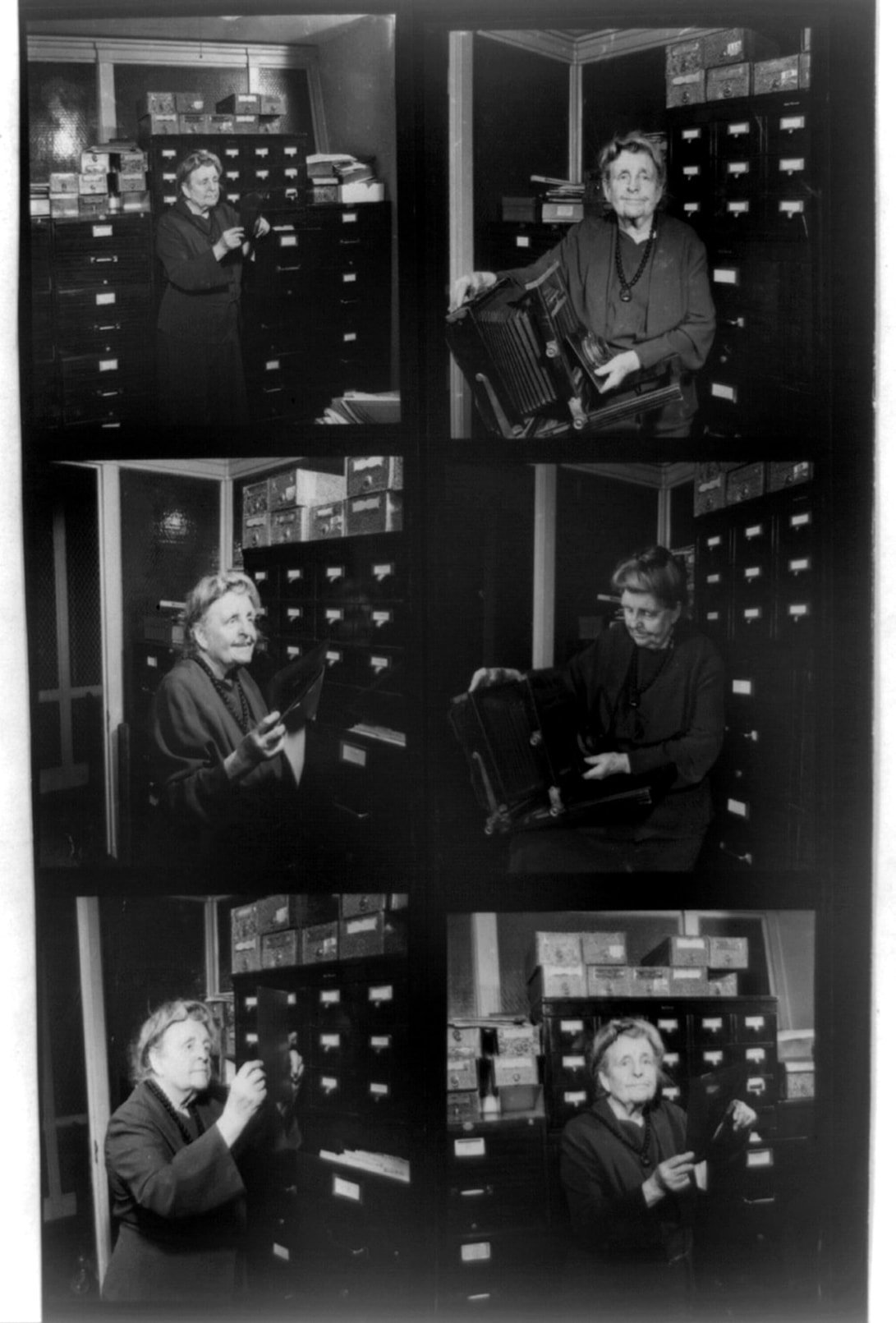

Frances Johnston in a series of self-portraits taken in the 1940s. Library of Congress

Happy to have sold the house, the agent leaves, sauntering down Bourbon with the distinct impression that this elderly, strong-willed woman, with her glass of whiskey, burning cigarette and no-nonsense attitude, was a force of nature.

He had no idea.

Meet Frances Benjamin Johnston, the most famous lesbian you’ve never heard of.

Born in 1864 in Washington, D.C., Johnston became one of the nation’s first photojournalists, an accomplishment in an era when both photography and journalism were decidedly male professions.

Frances Benjamin Johnston self-portrait, 1890s, Library of Congress

"Look! Look!! Look!!!" Frances Benjamin Johnston, entrepreneur, 1903, Library of Congress.

After studying art in Paris in the 1880s, Johnston returned home to establish herself as a professional portrait photographer. Among her clients were U.S. Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt. She is regarded by many as the the first unofficial White House photographer.

FBJ photographing unknown man on the balcony of the State, War and Navy building in Washington, D.C., 1888. Library of Congress

The Rough Riders, with Teddy Roosevelt in left center, by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1898, Library of Congress

Researcher and inventor George Washington Carver (front and center) poses with staff members of Tuskegee Institute's agricultural department in 1906. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston, Library of Congress

Susan B. Anthony by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1915 - 1920, Library of Congress

Later, Johnston turned her camera toward documentary work, photographing day-to-day life in public schools and the working conditions of miners. The architecture and gardens of the post-reconstruction South fascinated her, an interest that led to her establishing the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South — a sweeping project that pictorially documented over 1,700 sites in nine Southern states.

Visiting New Orleans in 1938 for an exhibition of her work, Johnston was easily and utterly captivated by the old-world charm of the Quarter, smitten by its extraordinary architecture and eccentric characters.

Frances Benjamin Johnston self-portrait, 1880s, Library of Congress

What must have been a shocking photography in the Victorian-era 1890s - two women kissing. Note the apple in the photograph, seeming to suggest lost innocence. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston, Library of Congress

Another daring Frances Benjamin Johnston image from the 1890s, perhaps suggesting Athena and her owls, symbolizing wisdom. Library of Congress

The Quarter Johnston discovered had other appeals as well, namely a thriving arts scene and a libertine atmosphere that defied conventional morality. It was during this visit that Johnston probably met Pops Whitesell, a fellow photographer and French Quarter fixture.

Joseph Woodson Whitesell moved to New Orleans from Indiana and quickly became a part of the French Quarter Renaissance of the 1920s. Writing in 64 Parishes, John H. Lawrence notes, “Whitesell’s photography achieved international recognition in professional salon exhibitions. In 1947, he was the ninth most exhibited salon photographer in the world.

"According to articles published in his lifetime, a charming demeanor and impish appearance made him a universally popular figure among his neighbors in the French Quarter, high society clientele, celebrities from the world of arts and letters, and fellow photographers.”

When not photographing Uptown society matrons and Carnival royalty, Whitesell photographed nearly nude, oil-slicked male models for muscle magazines, the closest thing to gay pornography at the time.

Whitesell opened his studio in 1921 at 726 St. Peter Street, behind what is now Preservation Hall. Neighbors affectionately called him the Leprechaun of St. Peter Street because of his diminutive stature and rakish nature.

Not far from Whitesell’s studio was the influential Arts and Craft Club, located on Royal Street in the famed Seignouret-Brulatour house. A few doors down, writer and local bon vivant Lyle Saxon hosted regular cocktail parties and literary salons. The group of bohemians that coalesced in the Quarter in the 1920s included Whitesell and several other gay men including Lyle Saxon, W.R. Irby, Cicero Odiorne, Weeks Hall, and William Spratling.

Portrait of writer Lyle Saxon (1891 - 1946) by Whitesell, 1930s. On the back is written, "The Last Photo of Lyle Saxon."

By the time Frances Benjamin Johnston settled in New Orleans, Whitesell was the last man standing, a holdover from the glory days of the 1920s. The two became fast friends and lived out their last years in the Quarter — Johnston died in 1952, Whitesell in 1958 — and one imagines these two queer photographers passing their days in Johnston’s courtyard or perhaps having cocktails at Café Lafitte, the de facto gay bar of the era, located in what his now Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop.

Johnston's Bourbon Street house, late 1840s, Library of Congress

The courtyard of Johnston's Bourbon Street house when she purchased it in 1946. Photo by FBJ, Library of Congress

The courtyard of Johnston's Bourbon Street house after she restored it. FBJ photo late 1940s, Library of Congress.

A parlor in Frances Benjamin Johnston's Bourbon Street home, circa late 1940s. Library of Congress

Johnston wrote in a letter to a friend that she lived “in walking distance of the best spots of the Vieux Carre, two blocks from the French Market and the Morning Call, where you can get coffee and donuts at 4am.” (Quoted in Berch).

It’s heartening to envision these two aging nonconformists drinking coffee by the river after a night of carousing, watching the sun rise over Bienville’s “beautiful crescent,” perhaps reflecting with gratitude on lives well lived and the quirky neighborhood they called home.

Frances Benjamin Johnston when she was about 40 years old, in 1911. Photograph by Will Towles, Library of Congress