In Memoriam: Lost Lands

This modern-day rendering by New Orleans artists Jim Blanchard depicts the James Muggah family's new and improved hotel on Isle Derniere. Never realized, construction on the expanded hotel was set to being at the close of the 1856 summer season. The Muggahs had contracted with the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans to manage the project and had collected a consortium of eager investors. Ironically, the hotel was to have been called The Trade Winds.

August 2020As the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina approaches, a look back at the unnamed 1856 storm that erased the Island of Derniere off Louisiana’s coast, taking the lives of more than 400 people, including thirteen ancestors of the writer.

- by Bethany Ewald Bultman

- illustrations courtesy Bethany Ewald Bultman

Monday, August 10, 2020

One hundred and sixty-four years ago today (1856), at 6pm, 13 of my ancestors lost their lives in a hell-binder of a hurricane that bore no name. That morning being Sunday, they had attended a simple Protestant worship service in the parlor of the hotel they owned on Isle Derniere, a lush barrier island 30 miles off the coast of Morgan City.

As the sky turned dark, with the wind gusting and the Caillou Bay churning, they ate their leisurely Sunday dinner in the dining room as bored, ringleted children rampaged around the veranda, disrupting the naps of the shhhhhushing elders in their creaking rocking chairs.

By afternoon, saltwater covered rose gardens, the racetrack, and rows of pole beans and tomatoes. Survivors would later confess that they didn’t see any reason to think this wasn’t just another typical August storm. Some of the anglers were even braving the heaving breakers to land whopping red fish.

By 9pm, the expanse of beach where they had skylarked the day before on prancing ponies beneath sun-crested trees was strewn with 400 mangled corpses, mingled with debris of man’s folly and the putrid carcasses of dogs, horses, cattle, and thousands of birds and fish.

The island was reduced to 75 square feet of sand by a tidal wave that erased man’s footprint. It was the worst storm to hit Louisiana in the 19th century.

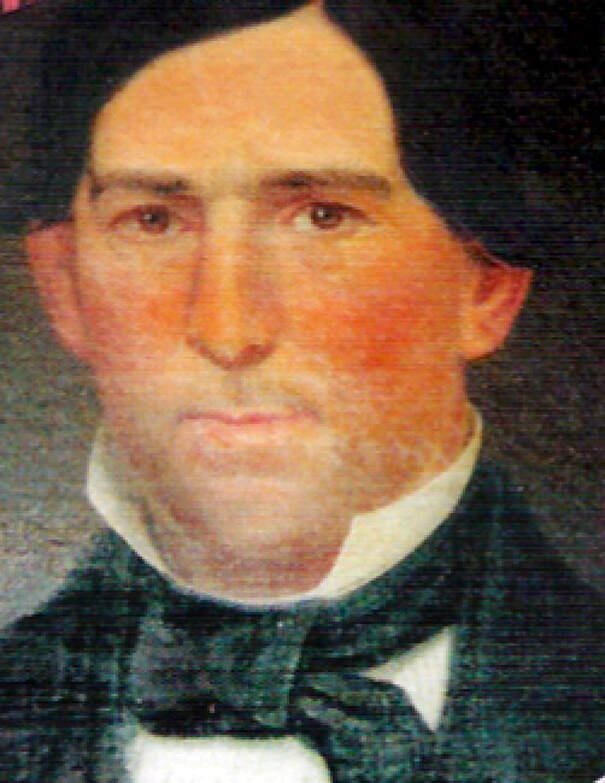

James Milne Muggah (1806 - 1856) and his son Charley (1848 - 1856). Ancestors of the author, James and his son died with his brothers, sisters-in-law, nieces and nephews. James left his young widow, Julia Curtis, to raise their three daughters and her two step-children.In my childhood, August 10 was a day of mourning for those lost at Isle Derniere. Now, my grief on this day is for the folly of my family and all those lost because of their trespass on a fragile barrier island, our wetlands and coastline.

While Louisiana has 40% of the country's wetlands, more than 90% of the total coastal marsh loss in the continental U.S. occurs here. That means every 100 minutes, we lose the equivalent of one football field of land into the Gulf of Mexico. Since the 1930s, Louisiana has lost close to 2,000 square miles of wetlands, an area roughly the size of Delaware.

Natural causes include hurricanes, saltwater intrusion, subsidence, wave erosion and sea level rise, but human activities are most responsible for accelerated coastal land loss. It is due in large part to our “trespass.” Today, because of canals and levees that constrict and confine the path of the river, the sediment cannot reach the delta to replenish the eroding wetlands. Floods from storms are far worse as we cut trees, pave open spaces and “develop” our wetlands.

Louisianans are no strangers to the dire consequences of trespassing on fragile coastlines, since some of the deadliest tropical storms and hurricanes ever to hit the United States have struck the Louisiana shoreline.

Less than 50 years after the Isle Derniere hurricane, neighboring Texas suffered the deadliest storm in American history: the Galveston hurricane, which killed 8,000 - 12,000 people on Sept. 8, 1900.

Then on September 20, 1909, the Grand Isle hurricane struck the Louisiana coastline. Grand Isle was completely devastated before the Category 4 hurricane moved across the state to slam New Orleans. More than 350 people died in the coastal parishes due largely to the 15-foot storm surge. Because low-lying areas within the city limits at that time had little residential development, the consequences of the flooding were much less severe than those of Katrina.

Hurricane Audrey struck on June 27, 1957, making it the strongest hurricane ever to form in June. In the Gulf, monstrous swells of 45-50 feet were reported. More than 1.6 million acres were flooded by the storm surge and headwater. High winds in Baton Rouge blew out windows from the skyscraper capitol. One of the more curious aspects of Audrey was the exodus of wildlife preceding it. On the evening before landfall, thousands of crawfish were seen fleeing the marshes around Cameron.

By the time Hurricane Betsy came ashore on Grand Isle eight years later, folks had begun to let their guard down. On Sept. 9-10, 1965, this hurricane hit Louisiana with winds gusting to 160 mph and dumped 12.21 inches of rain on New Orleans. A ten-foot storm surge caused New Orleans’ worst flooding in decades. The city spent days underwater with flood depths reaching up to nine feet in eastern New Orleans and Chalmette. Across Louisiana, 2.4 million acres were inundated by the storm.

Four years later on Aug. 17 - 18, 1969, Hurricane Camille, the most intense hurricane ever known to make landfall in the United States, made its mark on Louisiana. Winds gusted to 125 mph at Slidell. Almost total destruction was seen from Venice to Buras as intense winds estimated at 160 mph moved into lower Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes. A total of 860,000 acres of land was flooded in Camille’s storm surge.

Katrina roared ashore 15 years ago this August 29. And this year, it is predicted that we’ll have more than 21 named storms — storms that will affect all races and socio-economic classes profoundly and indiscriminately.

So on this day, August 10, 2020, I pray that our “next normal” values preserve and protect the land we have left.