How Emilie Rhys Found Her Father – and Her Groove

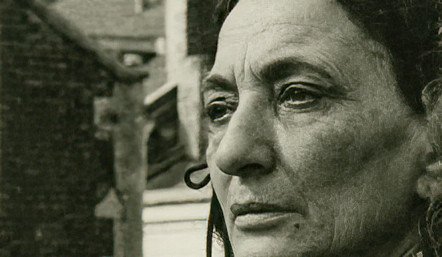

Rockmore and Emily on Jackson Square in the summer of 1977. Courtesy Emilie Rhys

January 2025Seeking a relationship with her estranged father – the noted New Orleans painter Noel Rockmore – a young woman travels to the Quarter in 1977 for a year of discovery.

– by Michael Warner

It’s hard to know where you’re headed if you don’t know where you’re from. So in September 1976, 20-year-old Emily Davis left her West Coast home seeking missing parts of her background. She first headed to New York City, where a noted artist held the key to her past. The man was Noel Rockmore, her father.

By February 1977, she was living with Rockmore in New Orleans, where the artist had lived part-time since 1959. Barely out of her teens – Emily – who later adopted the name Emilie Rhys – knew her father’s name and had seen a little of his art. But her mother had rarely spoken of him after their painful marriage had broken up 18 years earlier.

Rockmore was an ingenious painter and draftsman, as well as an accomplished violinist; no dimension of his life was small. He prodigiously created painting after painting, often in massive formats. While he could express great joy, he sometimes withdrew into long-smoldering anger. His vast ego was impossible to caricature. He sometimes bragged that he had gone to bed with thousands of women. Often self-destructive, he nurtured a deep and enduring loyalty to his friends.

Artistic talent ran strong in Emily’s family. Her father was the son of two well-known East Coast artists, Gladys Rockmore Davis and Floyd Davis. Gladys and Floyd met at the Grauman Brothers advertising firm in Chicago where they were both employed, and by 1925, they married. Noel was born in 1928 and his sister, Deborah, arrived in 1930.

Family photos in Emilie’s studio show Noel Rockmore playing violin as a child and a photo of Gladys and Floyd Davis with Noel and his sister as children, featured in Life magazine.

Floyd had left high school at an early age to help earn an income for his family. He had a keen interest in draftsmanship and largely taught himself the craft. He established a lifelong career as a commercial illustrator, and his work is still collected today.

A self-portrait of Gladys Rockmore Davis hangs in Emilie’s home

Gladys had studied at the Chicago Art Institute and, later, at the Art Students League of New York. She began her career as a fashion and commercial artist. But a year-long trip to the Côte d’Azur of France for the entire family in 1932 exposed Gladys to Impressionists, Expressionists, Fauves, Nabis, and other styles of work that were totally removed from what she had been creating. When they returned to the States, she no longer worked for advertising firms and turned instead to a career in fine art.

After Allied forces liberated the North of France in 1944, Life magazine sent Gladys and Floyd to Paris to document the restoration of the city. That made Gladys the first female accredited wartime artist-correspondent for that publication.

Photos of Emilie’s grandparents in her book, New Orleans Music Observed, the Art of Noel Rockmore and Emilie Rhys

Noel followed in his parents’ fine art footsteps. As a young man, he married Elizabeth Hunter, a woman from a well-established family, and they had three children. His career began to blossom. By the mid-1950s, he had held well-received shows at New York’s Salpeter Gallery and was included in group shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art.

A photo of Rockmore playing for his young family in Emilie’s book, New Orleans Music Observed, the Art of Noel Rockmore and Emilie Rhys

Emilie’s family art wall, with work by her father, aunt and grandparents, photo by Ellis Anderson

But in 1958, driven by ambition, old friendships, and his ego, Noel left Elizabeth and their children. A year later, he moved to New Orleans. Thereafter, Elizabeth avoided even mentioning his name.

Which was not the one he’d been born with. In the 1950s – and to his parents’ chagrin – Noel changed his surname from Davis to his mother’s family name – Rockmore. He claimed there were too many Davises in the New York art world (in addition to his parents and sister, noted artist Stuart Davis were all working on West 67th Street).

Emily and her siblings grew up essentially having never known Rockmore. But that was soon to change.

Driven by a need to learn about their father, Emily and her brother Chris – a few years older than her – had reconnected with Rockmore individually. A plan was hatched for the kids to join Rockmore in New Orleans for the spring and summer of 1977.

Emily arrived in New Orleans first, already an artist with raw talent and a natural gift for portraiture, one who was quite comfortable with a pastel stick in her hand. When she arrived at New Orleans Airport, she was greeted by a woman named Gypsy Lou Webb. Rockmore had arranged for Lou to receive Emily because he was out of town, in the process of closing out his New York studio.

Gypsy Lou Webb. Read a 1995 interview with her by Dennis Formento here. Detail of a photo by Johnny Donnels, The Historic New Orleans Collection

Lou was slim, in her early 60s. Her dark hair and penetrating eyes had inspired Bob Dylan to describe her in song. She was an artist, a Bohemian. With her husband, she established Loujon Press and published the ground-breaking literary journal, The Outsider. She knew Kerouac. Hemingway. Tennessee Williams. Henry Miller. William Boroughs. Charles Bukowski.

Lou took Emily to stay at her third-floor two-room apartment at 640 Royal Street - what locals sometimes refer to as the “first skyscraper” because it was one of the tallest historic buildings in the neighborhood. In Lou’s small apartment facing the courtyard, Emily settled in until Rockmore returned from New York.

The “Skyscraper” building at the corner of Royal and St. Peter, 1977. Photo Vieux Carre Commission Library

The Skyscraper Building housed a thriving Bohemian community. In an apartment down the courtyard from Lou was etcher Howard Mitcham. Mitcham was also a gourmet cook, poet, and author. He ran a “cooking laboratory” on the third floor of the Skyscraper, where he prepared and tested hundreds of recipes as research for his cookbooks. Photographer Johnny Donnels maintained a studio in the building, while another denizen, Darlene Doherty, modeled nude for Donnels’s photographs.

Not long after Emily’s arrival, Lou assigned her a project. “That wall out there on the balcony, it's so bare,” said Lou. “Why don't you paint something on that?”

So as she awaited her father’s arrival, Emily composed a mural of herself with Rockmore, and Gypsy Lou and others in the building. Darlene makes an appearance as a mermaid. Another of her dad’s friends is depicted in the mural. Bob Page was a retired merchant marine and a primitive artist in his own right, who Rockmore called Old Man or OM. Emily thought his warm, friendly face looked “about 110 years old” from hard living.

Young Emily Davis, shortly after arriving in New Orleans in February 1977, painting a mural outside Gypsy Lou Webb’s apartment, photography by Johnny Donnels, courtesy Emilie Rhys

The mural in 2024, after Emilie restored it. Old Man is on the left, Emily and Gypsy Lou flank a scowling Noel Rockmore. photo by Ellis Anderson

Returning from New York in March 1977, and flush with money from the sale of his studio, Rockmore moved Emily to live with him in a grand townhouse on the 900 block of Orleans Avenue in the Quarter, just a few blocks from Jackson Square. Emily was impressed by the home’s double parlor and its twin fireplaces and ornate chandeliers.

It’s there that she helped her father finish an ambitious 4-ft x 12-ft mixed media work on canvas entitled “Bourbon Street Parade,” presently on display at the New Orleans Jazz Museum. In the process, the artist came to recognize Emily’s talent.

When Chris arrived in New Orleans, the artist found a small apartment on Royal Street for his son. “He didn't want me to be living with him and Emily because Noel was bipolar and his tirades would just kind of erupt unexpectedly,” Chris said in a recent interview. “And he thought apparently that I wouldn't have put up with them.”

Rockmore had another close friend, artist John Miller, who sold pastel portraits along the fence at Jackson Square. Rockmore asked Miller to help his daughter and son to set up their own stations on the Square. Emily specialized in portraiture, while Chris struggled to follow suit. He didn’t share her flair for capturing likenesses, and when he gave up his spot on the Square, he began creating exquisite drawings of New Orleans’ hauntingly beautiful cemeteries and quick sketches of people lounging on benches and in cafes.

Most days, Emily jig-sawed chairs and pastels, paper and easel into a metal shopping cart, which she could push to her spot on the fence. She soon developed a habit of arriving at the fence in the small hours each morning – as artists still do today – to stake out a choice location. Her favorite spot was at St. Ann Street near Chartres, where she could later catch a spot of shade from the afternoon sun.

Emily Davis on Jackson Square in 1977, photo courtesy Emilie Rhys

Though already a good artist, the work on the Square forced Emily to focus on her technique, to turn it into a profession. It was the first time she regularly made money off her work – a living income. She had sold a few works before, but it was nothing like the “day-in and day-outness” of working “on the fence.”

Emily’s copy of the Rembrandt self-portrait that she used to interest customers. Courtesy Emilie Rhys

To attract business, Emily displayed some of her work, including an exceptional pastel copy of a Rembrandt self-portrait. Her father’s friend, OM, came to chat and shill for her by posing for a pastel portrait first thing each morning. Tourists would line up to watch. And then they’d want one too. Most portraits took twenty or thirty minutes.

“They talk about the 10,000 hours of the Beatles and how the band built that knowledge and confidence and ability in Hamburg,” said Emilie, in a recent interview. “I feel like my first experience of something akin to that was being on the Square and working so hard every day, building those skills and my confidence.”

And she made money. Lots of money, for a kid just out of her teens. “At a certain point I was tripping over this stash of money that I would throw under the rug in my little room,” she said. “It became a mound.”

Working day in and day out, Emily didn’t have time to do anything with her newfound wealth. “You'd think I’d have stashed it in a bank account,” she recalled, laughing. “But I didn't even have one yet.”

Emily Davis, at her easel painting a self portrait in her father’s townhouse on Orleans Street, 1977, photo courtesy Emilie Rhys

Late in the summer, as Emily sat at her spot on the Square, she was approached by an extraordinarily tall man. An absurdly tall fellow. Pro-basketball tall. He was with an entourage, and as he walked up and down the Square, he examined the displays, sometimes chatting with one artist or another.

The man stopped with Emily before wandering off to visit other portraitists. But he returned. And he gave Emily a $100 bill and two hours later, he left with his portrait. To this day, she doesn’t know who it was.

Emily’s father would sometimes come to the square to watch his daughter work. According to Chris, she was attracting crowds of admiring onlookers, many staying to watch till she finished a portrait. Applause would follow. Rockmore sometimes laughed at her, in a sort of jealous derision, but his daughter refused to be marginalized.

Portrait of Chris Davis by Emily Davis in 1977, New Orleans, courtesy Emilie Rhys

Self-portrait by Emily Davis in 1977, New Orleans, courtesy Emilie Rhys

The jealousy extended to their attention – Rockmore craved the full devotion of Emily and Chris all for himself. He didn’t encourage them to develop friendships outside of his entourage. Chris remembers, “I think Noel kind of wanted us to just be in his world. And by his world, you know, paying attention to him.”

Emily also felt the force of Rockmore’s ego. “He was such a bombastic personality. There would be a lava flow because his furies would be extended, happening over a period of time.”

And then there were Rockmore’s frequent bar fights, which he made a habit of losing.

An enlarged contact sheet of Noel Rockmore and Emily Davis in 1977 from the 2020 exhibit in the New Orleans Jazz Museum, “New Orleans Music Observed: the Art of Noel Rockmore and Emilie Rhys.” Today it hangs in Emilie Rhys’s gallery, photo by Ellis Anderson

By fall, Emily had accomplished everything she had sought when she’d arrived in February. She had created the Skyscraper mural and helped with the “Bourbon Street Parade” painting with her father. She took on a series of portrait sketches of early jazz musicians for inclusion in Mitcham’s book, Creole Gumbo and All That Jazz. She had worked full days on the Square. The admiration tourists had shown in her work had stoked her confidence and she’d earned an income that made the now twenty-one-year-old feel rich.

Emily had also accomplished her goal of getting to know her father – for better or for worse – finding both positive and challenging aspects in his personality. Emily had worked side-by-side with Rockmore, learning from him and participating in the creation of iconic works. He had helped her get a start at the square. Yet, overall, the relationship was emotionally draining.

Noel Rockmore and Emily Davis working on the Bourbon Street Parade mural in 1977. From an enlarged contact sheet displayed in Emilie Rhys’s Royal Street gallery.

Noel Rockmore and Emily Davis working on the Bourbon Street Parade mural in 1977. From an enlarged contact sheet displayed in Emilie Rhys’s Royal Street gallery.

“Initially, he was insulting on occasion,” she remembers. “And as time passed, he built to a crescendo of vitriol so vile it was impossible to withstand.”

Noel Rockmore and Emily Davis on St. Peter Street in 1991 by John Heller, courtesy Emilie Rhys

Around November, Chris and Emily left New Orleans, having learned enough of their father – enough so that she did not communicate with him for about a year. Emily and Chris each continued their artistic careers. Chris currently lives in Brooklyn, NY, and shows his work at Carter Burden Gallery in New York City. In 2011, Emily (now Emilie Rhys) returned to New Orleans where she has operated SceneBy Rhys Fine Art (1036 Royal Street) since 2016.

It would take years for the father and daughter to reconcile, after Emily became an established artist in her own right. The two became close. Before the end of his life in 1995, Rockmore finally expressed admiration for Emily’s evolution from a shy kid to a professional fine artist.

Perhaps as important as anything: during that magical, aggressive, discovery summer, Emily began to blossom into the professional artist she’d eventually become, Emilie Rhys. Her time in Jackson Square remains at the center of her early artistic development – as it is for many New Orleans artists.

One of the most striking things she learned that summer was that portraiture on Jackson Square was generational.

“People who chose me to do their portraits often would say their parents had brought them to Jackson Square as children to have their portraits done,” she said. “And now they were coming back with their kids. So I thought that was really wonderful continuity.”

Today, Emilie’s French Quarter studio is also on Orleans Street, just a block away from the townhouse she shared with her father in 1977. As she walks from her studio to her Royal Street gallery, she traces the same path she walked decades ago, pushing her shopping cart brimming with the accouterment of a Jackson Square artist.

“Walking on that street, going toward that place, reconnects me every day with my younger self,” Emilie said. “We all carry a younger self within us, but I couldn’t connect with mine until 2011 when I moved back to the Quarter and began forging a life that included him [Rockmore] but wasn’t ruled by him.

“Some people have a hometown they can go to,” she continued. “When I was young we moved around too much, so I didn’t have that. But my 20-year-old self bonded so strongly with the French Quarter! When I moved back it felt like the prodigal daughter returning. I felt like I’d come home.”

Emilie Rhys in her gallery, 1036 Royal Street, 2025, photo by Ellis Anderson

Mitcham, Howard. Gumbo Creole and All That Jazz. Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1978, 22

Your support makes stories like this one possible –please join our Readers’ Circle today!