The Ultimate Outsider: A 1995 Interview with Gypsy Lou Webb

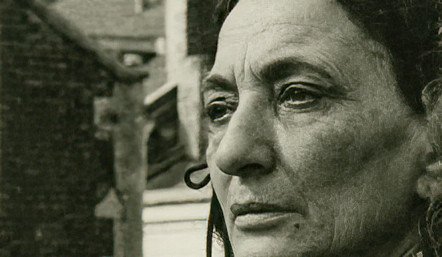

Gypsy Lou Webb, detail from a photograph by Johnny Donnels, 1975. Courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection

November 2023In the 1960s, “Gypsy” Lou Webb and husband Jon Webb worked out of a tiny French Quarter apartment and published ground-breaking work by beat writers like Charles Bukowski, Henry Miller, Langston Hughes, and Jack Kerouac. Thirty years later, she looks back at her literary life in New Orleans.

-by Dennis Formento

How I Met The Outsider

I first met Louise “Gypsy Lou” Webb when I interviewed her in the early ‘90s for my magazine, Mesechabe: The Journal of Surregionalism. I was interviewing people who had been involved in independent publishing, art, writing, music – anything that existed outside the pale of corporate American culture. This included communards, revolutionaries, counter-capitalists, bohemians, surrealists and third-world nationalists.

My first interview for Mesechabe was with John Sinclair of the Detroit Artists’ Workshop, who moved to New Orleans in 1991. This was followed by Ed Sanders of the Fugs, who was in town for a reading at Loyola University. And then came Lou Webb, who inspired me to look more closely at my own home town.

I knew who she was and what she’d achieved. When I was in college at the University of New Orleans in the late ‘70s, I used to spend a lot of time goofing off in the library, where a complete collection of The Outsider could be found in the stacks. I read many of them and always hoped to find loose copies somewhere. Never did – nothing I could afford anyway. Her work with husband Jon Webb in Loujon Press and The Outsider influenced my own work as an editor and publisher because many of the writers they published were major influences on my own poetry: Ginsberg, Creeley, Charles Olson. Any counterweight to the official magnolias-and-mint julep literary culture was welcome.

To find Lou, I got in touch with Jeanne Northrup, a mutual friend, whom I’d known from Leonard Peltier Committee events. She introduced us. Lou and I met at a coffee shop in Slidell. My partner at the time, Susan Ferron, came along and participated in the interview as well. Lou was a gas. She never missed a beat – she had a sense of timing that great drummers and storytellers have. I hope I have as sharp a memory at that age as she had.

L to R, Patricia Hart, Gypsy Lou Webb and Dennis Formento in 2007, photo courtesy Dennis Formento

After Katrina, Lou applied for a FEMA trailer that ended up in our driveway, but she never moved into it. Which was fine, because FEMA never finished the work and anyway, those things reek of formaldehyde and she could have poisoned herself in there. We remained friends and saw each other periodically when she moved into her sister’s hurricane-damaged house. My wife Patricia and I sometimes took her out or met her and Jeanne for lunch.

We kept in touch when she left her sister’s house and moved into the Greenbrier Community. She gave Patricia her first dulcimer when an admirer at the Greenbrier gave Lou a hand-made instrument – and how did Lou know Patricia really wanted a dulcimer? Pure chance, pure surreal hasard – a touch of the marvelous.

In between her sister’s place and the Greenbrier, Lou lived in a section 8 apartment with her little Chihuahua – one of a line of nasty little dogs who protected her with bared teeth and never accepted the bearded stranger who came to talk a while with Lou or take her out for a meal. Lou still ratted the streets of the Quarter from time to time with Jeanne and other friends, drinking, gambling, throwing the caustic remark your way. At 96, she could still play the game.

At 104, she came to the end of the line, silent, under a blanket at the Greenbrier, with a stuffed dog on her stomach—when I asked about it, she patted it as if it were real and smiled.

The last time I saw her, she didn’t move. The stuffed dog was missing. When I spoke to her, Lou turned her face at last to look at me, then she shooed me away with a hiss. Lou was a tough one.

An Interview with Louise Webb

The first small press revolution was fought with typewriters and mimeograph machines in the back-a-towns and bohemias of America. When it came to New Orleans, it was fought with a nine-by-twelve-foot offset press operated by novelist Jon Webb and his wife, painter Louise Webb, whose flamboyant style earned her the nickname “Gypsy Lou.”

Their Loujon Press produced The Outsider, a magazine of new writing, from 1960 until 1968, featuring writers such as Kenneth Patchen, Margaret Randall, and the Beats, as well as local and unknown poets. The Outsider was one of the first small magazines to give space to Charles Bukowski, both in the magazine and later, with “It Catches My Heart in its Hands,” in book form. The Webbs also published work by Henry Miller.

The French Quarter was a thriving enclave of musicians, painters, and writers amid the insanity of Jim Crow Louisiana. Tennessee Williams and surrealist photographer Clarence John Laughlin lived there. During the ‘50s and early ‘60s, New Orleans reigned as the R&B capital of the world with its capital at Cosimo Matassa’s recording studio in the Quarter – before Motown and Philadelphia locked up the title for the next two decades.

Robert Head and Darlene Fife soon followed the Webbs with NOLA Express, one of the great underground newspapers of the decade. NOLA Express also printed “Notes of A Dirty Old Man” articles by Bukowski, sending him his first paycheck as a writer, 25 bucks in mid-’60s dollars for a clutch of poems.

After their four-decade residence in New Orleans, the Webbs moved frequently, living in Albuquerque and Tucson, and enduring a flood that destroyed mounds of their work. Both grew sick, and Jon Webb died of a carotid artery blockage in 1971. The Wormwood Review honored Jon with a special memorial issue.

Wayne Ewing’s documentary, The Outsiders of New Orleans: LouJon Press, tells Lou and Jon’s story and includes footage of the gorgeously designed, hand-printed and boxed books by Henry Miller and Bukowski, which LouJon produced in the Quarter and elsewhere [we’ve included a link order from the filmmaker at the end of the interview].

In 1995, Louise Webb lived in Slidell, Louisiana and spoke with New Orleans poet Dennis Formento and Susan Ferron on August 9 of that year.

DF: I went into Dauphine Street Books and asked about copies of the magazine, and the owner, Steve Lacy, said he hadn't seen The Outsider. But later, a professor at the University of New Orleans, Kenneth Holditch, told me that he had been in the Librairie Bookstore and someone had just bought all of their Outsiders, and he heard it was you!

Lou: I don't have a one. I did give Edwin Blair (New Orleans bookseller) a whole bunch of them. I was real sick then and thought I was dying, so I thought I would give all the stuff to somebody who was really interested, two years ago. I had an operation, cancer of the lung. He's still got 'em, a lot of them.

DF: How did you go about finding such great writers?

Lou: Jon was a great letter writer. He'd write letters to the writers. He had subscribers who were interested in little magazines and a couple of writers that they liked, say, Ginsberg. And they would buy the magazine. One thing would go to another, and pretty soon he had a lot of them.

Did you know Wally Shore? He set the type at first on the magazine, when we first started. He moved out to San Francisco. I got a letter from him the other day. He wants to put out a magazine about the ‘60s. He wants me to write a letter of recommendation to Ferlinghetti for him. I said, "OK, you write it, and sign it!" I haven't heard from him.

DF: What brought you to New Orleans in the first place?

Lou: We were living in St. Louis for about a month. Jon was doing crime stories for True Detective and Official Detective. This other guy who invited us out there, Hal Zimmer, really wanted to know Jon's method, because he was good at it. We stayed about a month. Of course, we didn't have any money. I think we came down here with $17. We took a bus.

What happened was, we went to the bus station. Jon said, "We've got to get out of this place." And just then, a bus came by, called "New Orleans Express." We had never been to New Orleans. This was 1939. Jon said, "Do you want to go there?" I said, "Sure, how much is it?" We had enough to get a cheap room on Cleveland Avenue in New Orleans. With that 17 bucks, we got the bus fare and room rent for a week.

DF: You were here quite a while before you started The Outsider, but you didn't come for any reason but to get away from Hal Zimmer?

Lou: Oh, yeah! He was using Jon, because he was writing detective stories too. We figured we might as well leave while we had gotten a check for one of the crime stories. That's how it happened. I got a job. Jon was writing, his regular writing. We didn't do the magazine until the ‘60s.

You've got the Bukowski letters there? "Marina crying now as I write this. Now she has stopped." [Quoting from one in Screams from the Balcony: Selected Letters 1960-1970, Black Sparrow Press.]

That was his daughter, Marina Louise. He named her after me.

DF: Well, you've seen Neeli Cherkovski's book; there are photos of Marina and Linda. You published It Catches My Heart In Its Hands.

Lou: And Crucifix in a Deathhand. Barfly – I did see that [movie]. I thought that guy, Mickey Rourke, looked just like Hank. He acted like him and sort of loped like Hank. He did a good job. How come I don't have this? [Screams from the Balcony] I tell you, honey, I've been moving around a lot.

Lou with Charles Bukowski, gift of Edwin J. Blair, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

DF: This name is unfamiliar to me: Kaja (kayjay).

Lou: Kay Johnson. She lived in the Quarter. She was in love with this Corso guy. She followed him all over; she went to Paris, wherever he went. When she went to Paris, she was living on Ursulines Street. We were ready to move from Royal Street and she said, "Why don't you all take my place?" It was a three-room place in the back, kind of run-down, but the rent was only $40 a month. One room was the press, one was the kitchen, with all the plates around. The collating we did in the kitchen. And then the bedroom, and that was it. 618 Ursulines. They redid it, but it was run-down when we lived there.

DF: Did you go to the Bourbon House, the bar?

Lou: Yeah, yeah! That's where Jon and I met Tennessee Williams, at the Bourbon House. At that time, the late ‘40s, ‘50s, all the artists, all the writers, lived in the Quarter. It was cheap. Everybody congregated at the Bourbon House, or we'd go to Pat O'Brien's. That used to be where all the locals used to go. Now it's strictly tourists. Anybody who came to town, they'd automatically go to the Bourbon House.

DF: Are you familiar with people who put out a magazine called Climax, Del Weniger and Robert Cass?

Lou: I do remember him [Cass] coming over when we were on Ursulines. He'd come in, he would be getting tentative plans from Jon about the magazine. Jon would always say, "Bob is here.” I'd always say, "Throw him out." I was always throwing everybody out. Anyway, that's past.

Bill Corrington – I sent her [Corrington’s wife] a copy of Four Steps to The Wall (a prison novel by Jon Webb), a screenplay, before Bill Corrington died, years ago. She had moved out to California. And I thought, well, maybe she'll meet somebody and say she knew Jon. I don't know how many times I wrote to her and said, "Please send the script back." Bukowski didn't like him – Bill Corrington – too much.

DF: He wrote the introduction to It Catches, though. It seemed like an odd match – he was a Golderwaterite or something? Why did he write the introduction?

Lou: He wanted to. But Bukowski didn't like him. He thought he was a lousy writer. Douglas Blazek – he's the guy who helped us get the press.

DF: It was a huge thing. You set the type by hand.

Lou: Wally Shore did it at first. But he drank a lot of wine. I used to pay him a couple of dollars. I'd sell my paintings and go home, and Wally would be there drinking his wine, setting the page up, and I'd pay him for setting the page. He'd go get more wine.

So then finally I thought, "All I have to do is watch him. I could do that myself," which I did. I'm a good typist. So I figured if I'm that good on the typewriter, I could set type. I watched him two or three times. Finally, I said, "OK, you can go now! I can do it."

Lou at the press in 1961, gift of Edwin J. Blair, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection.

DF: You lived hand to mouth. Everything went into the press.

Lou: Everything I made on the corner. I had enough for an art show on the wall outside.

DF: How long did you do that?

Lou: Sixteen years.

DF: Painting right on the spot?

A drawing by Louise Webb, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

Lou: Yes, outside. I used to breathe those fumes. Plus I smoked a lot too then. That's how I got cancer. A couple years, March 12, '93, since the operation. They took out part of a lung, the right lobe.

DF: Did you recoup your investments in the magazine? Did it allow you to break even, or was it always a money-losing proposition?

Lou: Well, we'd get subscriptions, and as we went on, we raised the price. The first issue was a dollar, I think. The next was a little bit more, the next was on even better paper, and it was a little bit more. We got all this stuff free, too. Now of course, they're all out of print, and they're real expensive.

DF: They're so beautiful. People gave you type?

Lou: No, we had to buy the type. But we got a lot of paper free from people that were interested.

DF: It was you and Jon doing the work, but there was a network of people keeping it alive.

Lou: Kept us going, yeah. And then we wrote an editorial. Everything I made I put back into the magazine, either buying the type or something. We finally sold the press in Albuquerque, New Mexico, years later.

DF: Those things are hard to move. If you're not going to be doing it, why bother?

Lou: That's what you think! We moved that darn press about five or six times. Each time it was about a thousand dollars to pack and ship it wherever.

DF: There was a little frontispiece in every number of the magazine, picturing a man crawling through a hole in a wall. And it had a caption: "Bravo, another escaping Outsider... enter, man, and be calmed!"

It seems that there was a need for these kinds of magazines then that people today might not be aware of, because publishing has become so much easier and freer. You can't get busted for printing four-letter words anymore.

Lou: We had plenty of "f's" in ours!

Lou in the studio of New Orleans artist Frances Swigart Steg, 1994. Gift of Edwin J. Blair, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

Lou in the studio of New Orleans artist Frances Swigart Steg, 1994. Gift of Edwin J. Blair, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

DF: What was the Quarter like then?

Lou: Nice. We never locked our door. People would stroll in.

DF: Del Weniger wrote a book about that scene. He called the Bourbon House "A Quarterite Place," and described this freewheeling group of people.

Lou: Everybody living there then had talent of some kind. They were either artists, painting, or they were writers or poets or people trying to do plays. They were all talented, creative people. It wasn't like now, t-shirt shops.

DF: You lived in an apartment that Jon claimed Walt Whitman lived in when he was a journalist in New Orleans. How did that come about? (1107 Royal. The Webbs lived in 1109.)

Lou: We had to move. We only paid $50. Joe Levinson owned the building. He had a lot of property on the other side of Esplanade. He knew we were interested in writing and everything, so he let us have it. It was a small apartment. Jon had the press in there, and he built a loft with a stair. That's where we slept. Real tiny kitchen. Ed's got a picture of it, I think.

Jon and Lou Webb at 1109 Royal Street, 1965, Gift of Edwin J. Blair, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

DF: The times are interesting: I have an idea of the late ‘60s, because I was a teenager then, and things were changing. But in the ‘50s it was still the segregated Solid South. Was walking from one side of Canal Street to the other like leaving the country?

Lou: Yeah, right. Once you left the Quarter you were in strange territory. And there was a lot of segregation then. Bourbon Street had a lot of Black people living on it. They were kind of scared of white people. I used to walk around any hour of the night. We used to walk around, Jon and I. We'd go into Black clubs and listen to music.

DF: You could have been arrested for just going into the wrong place.

Lou: We did get arrested one night, going to a club on South Rampart. It was Christmas Eve, and Jon knew this Black singer. He said, "Let's go find Joe and wish him Merry Christmas." I said, "All right." So we got all dressed up. He [Jon] drank a lot so we had to be in one place or the other. We went from one bar to the next, in the early evening, and then it got late and we still didn't find Joe. Jon was tired and he said, "You wait out here, honey."

We were in a Black neighborhood. So Jon goes in and says "Merry Christmas." So when Joe comes out with Jon to see me, out of the blue, there's a white cop standing there. He hits Joe on the shoulder with a billy club. Jon says, "What are you doing?" The cop says, "What's it to you?" And Jon says, "Well, he's my friend." He got mad, the cop. And of course, Joe, he's just standing there, scared to death. And me, I don’t know what the hell is going on.

Jon had his own ideas. He said; "He didn't do anything to us. We came to wish him Merry Christmas."

"Shut up," the cop says to Jon, "what are you doing in this neighborhood anyway?"

And Jon explained that we were looking for him because it was Christmas Eve. So the first thing you know, there was a box right there and he called for a paddy wagon. It came up, and the cop told Joe to get in, which he did. He was a big guy, oh, could he sing "Summertime." Joe Hart. And Jon said, "He didn't do anything." The cop said, "You get in there, too." So I'm alone in a Black neighborhood, and I said, "Can I go too?" "Yeah, you get in too." So we were all arrested.

I had on a satin suit, oh, was I dressed up. I had to give them all my money. They took my cigarettes away. The cop put me upstairs. There was a Black girl in the cell. He said to her, "Hey, so and so – get out!" The n-word. I really liked her in there – I could have someone to talk to. So I'm sitting there on the bed, and Jon's downstairs. They put him on the first floor. There were two Black guys in the cell next to me. We spoke, and I said, "Oh, I wish I had a cigarette, honey." And these two Black guys said; "Lady, would you like a cigarette? Go on over by the toilet, there's a little hole there. We'll pass a cigarette in through there." I said, "OK!" I didn't sleep, I just sat there. Pretty soon the white cop came by, and he was saying something dirty, referring to me. He opened up his pants.

So that morning, when they let us all out and gave me my money back, we got a cab. We said, "What are you going to do today, Joe?" He said, "I don't know." We said, "You're going to come with us, and we're going to have a Christmas dinner, all three of us, in our apartment."

DF: You got in touch with Bukowski because he was writing a lot of poetry, and you ended up publishing a lot of it.

Lou: Jon took most of it. Some of the stuff he sent back. We loved his stuff, but some of it was a little too much. We made him "Outsider of the Year." He fit the image. I remember going out to L.A. He had a bungalow, with all the empty beer cans to the ceiling, and then this Outsider plaque.

DF: Maybe I'm nostalgic for the critical mass of the period.

Lou: That's the thing, nostalgia. People are into these reveries of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Everybody wants to recapture it. They read about it and say, "Oh, that must have been a great time," which it was.

DF: You can't make history repeat itself, but you can reproduce situations that allow creativity to thrive. And New Orleans is a place where you can make things happen: it's still cheap to live here (in 1995) and people will listen to you. Why did you take the name, The Outsider?

Lou: Well, because we wanted stuff that wasn't normally published, something avant-garde.

DF: Jon had an argument in the magazine with poet Robert Creeley over what was new. Creeley was arguing for absolutely new writing, and Jon believed that whatever is being written now is new. From what Jon and Bukowski had written, it seemed they thought Creeley wanted to form his own movement. The Outsider published new writing even by Creeley's definition, and it had a real populist feel.

Lou: There are those types of writers who would look down on stuff like that, even what you're doing.

DF: You had Burroughs in there, who was publishing The Ticket That Exploded and Nova Express, creating new forms of narrative. But he's become an icon, like Bukowski: even people who don't read much know who he is. He's doing Nike commercials. Even Allen Ginsberg, the poet, has done a Gap jeans ad.

Lou: He (Ginsberg) came through Tucson and stayed at the College Inn near the university, with Peter Orlovsky (Ginsberg’s partner.). By that time I was sick with emphysema, real bad then. I remember him coming over one night, and he said, "Gypsy, what you've got to do," he was telling me how to breathe, and he'd say, "Aaah—ohhmm.'?

DF: Did it help?

Lou: Not really. It hurt real bad.

DF: We've talked to Ed Sanders, [poet and founder of the Fugs folk rock group] and Tom Dent [New Orleans writer and founder of BLKART - SOUTH] about their lives in the Lower East Side and Harlem in the early ‘60s. They spoke of the bars and coffee shops where people hung out, where you could show your paintings and talk for hours.

Lou: That's what it was. I remember Joe Donaldson was a famous painter, he's still alive, a good friend of mine. In fact, he asked me to marry him after Jon had died. He was the greatest watercolorist in the South. That's when I first met Joe. He drank a lot at that time, and he did beautiful paintings. And to pay the bill, at the Bourbon House, he'd give the lady a painting. That's how they did it.

DF: Like a barter system. Did you know of a magazine of the time when you arrived in the ‘30s called Iconograph? Kenneth Beaudoin was the editor. William Carlos Williams once wrote a favorable review of Beaudoin’s work. There was also The Double Dealer, that Faulkner was involved in, a few years before you arrived. Was there anything else going on here in publishing when you arrived that stands out?

Lou: We weren't publishing yet. Roark Bradford lived right on Toulouse Street. We got to know him. There were a lot of writers, but there was really not anything in the way of publishing. Actually, we met, as I told you, Tennessee Williams. He was writing. It was later when he wrote A Streetcar Named Desire. He was nice. He would go to Pat O'Brien's a lot.

DF: Did you know Clarence John Laughlin?

Lou: Oh, God, yeah. He was a pain in the neck. You ought to talk to Blair [Edwin Blair] about him. He lived in the Pontalba. We went over there one night, he was showing some of his photographs. He wasn't very friendly. I'd see him every now and then, running around the Quarter, but I didn't like him. Jon didn't like him. I don't think anybody liked him! I guess he was a good photographer. I liked his photographs..

Do you know Noel Rockmore? Do you ever go into Johnny White's Bar on St. Peter and notice the big reproduction? I'm the main character. Jon is the man in the beret. Rockmore did that. Sold the original for ten thousand. It's called "Homage to the French Quarter." They're all Quarterites in there. A lot of them are dead. He did this painting of me. Sold every damn one. He swore a lot, he drank a lot, fooled around a lot. He did everything a lot! But I liked him.

In 1977, Lou, a widow then, lived in the “Skyscraper Building” at 640 Royal Street, and many of her neighbors were local artists. The 20-year-old daughter of her friend, artist Noel Rockmore (center in mural, holding black dog), stayed with Lou for a few weeks in 1977 and painted this mural on a wall facing the courtyard. Young Emilie Rhys came into her own artistically and currently has a gallery at 1036 Royal Street. She restored the mural in 2020. Emily was twenty at the time and painted herself beside her father (blue shirt). Others depicted are French Quarter characters and artists. Photo by Ellis Anderson

Detail of Gypsy Lou with her dog from Rhys mural, photo by Ellis Anderson

DF: Eventually, you left the city and lived awhile in Tucson and Albuquerque. Tell us a bit about that.

Lou: We were living in Albuquerque, and Jon loved to go to Vegas. We ended up finally moving to Vegas, but this was before we moved there. He was working on a book, and he worked hard. We were living in a Chicano neighborhood, and they didn't like Jon because he was like your coloring, but they thought I was a Mexican. Maybe they resented him because he married a Mexican. So Jon had been working hard, and said, "Can I go to Vegas, honey?" I said, "Sure, Jon," and I gave him fifty dollars. So he took a plane, fifty minutes from Albuquerque to Vegas. He loved to play the dice.

About ten o'clock Jon called, and said, "Honey, I just wired you one thousand dollars." I said, "Oh, my God, that's great!" So I went back to sleep. And then the phone rang again. He did it four times. The second time he won another thousand, then I think he went across the street to the Fremont and he won two thousand there. And each time he wired it. He wired me $6,000 and he had gone with fifty bucks.

Well, morning came, and I was going down to collect. Jon called and said, "Honey, do you have cab fare for me?" And I said, "Yeah!"

He'd spent his $50 on the round trip. So I took the bus down to the Western Union. But they said they didn't have the money. I said, "What do you mean, you haven't got the money? My husband called and said he wired it." "Yes, yes, but you go next door to the Bank of Albuquerque." He sent it to them somehow. I said, "OK." And that's what I did.

I said, "Do you have $6,000 here for Mrs. Webb?" And they said, "Yes." So I said, "OK, just leave it there, put it in my book." And pretty soon, Jon came and I had to pay the cab. Oh, he was tired. He had bought $67 worth of books on gambling. And he read those things day and night. He said, "If I had known I could win that much money, to hell with the magazine and writing!"

Read more about Louise and Jon Webb in Bohemian New Orleans, by Jeff Weddle, published by University Press of Mississippi (2021).

This excellent documentary about the Webbs is available from filmmaker by Wayne Ewing.

Join our Readers’ Circle now!