The Last Forgerons

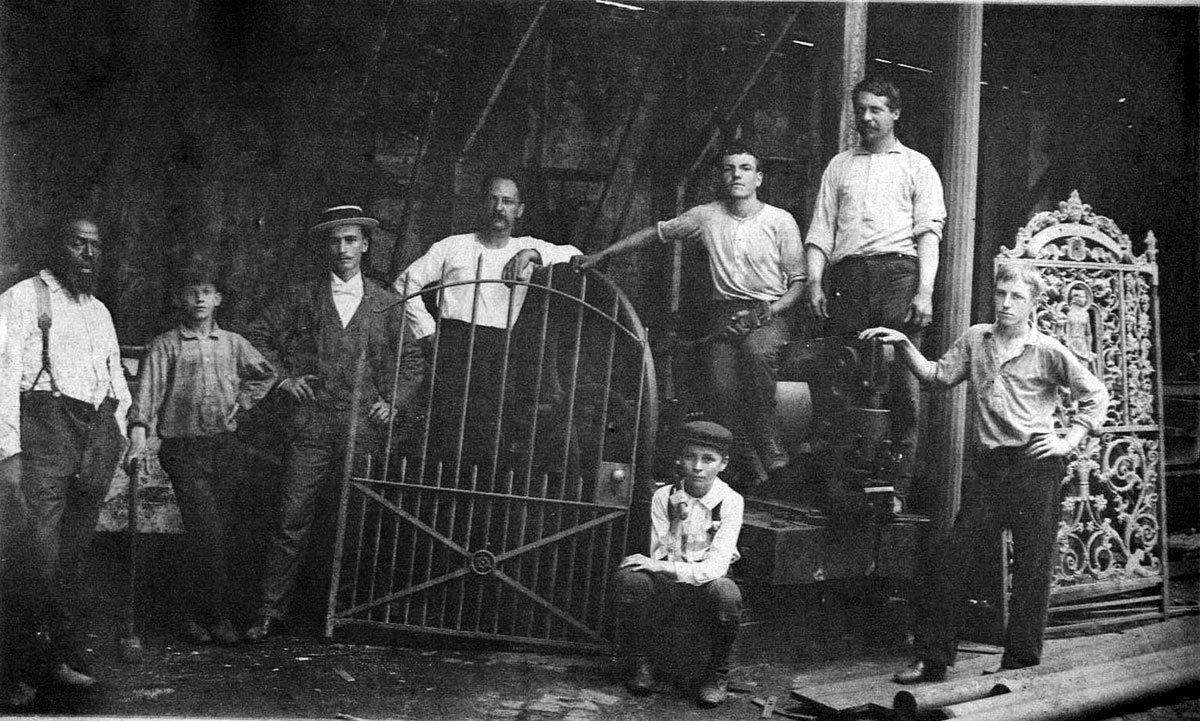

In the shop with other iron-workers, sometime before 1885. Charles Mangin (behind gate) and Jean Mangin (second from right). Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin. If anyone can identify the ornamental cast iron gate in the background please email us.

November 2023In 1920, the last in a line of French Quarter forgerons put down their hammers, never again to create the wonderfully detailed wrought iron fences and balconies of New Orleans.

– by Michael Warner

photographs courtesy Roy Arrigo, The Historic New Orleans Collection and Ellis AndersonCharles Antoine “Pine” Mangin, Jr. and his brother Jean Able “John” Mangin, Creoles and fifth-generation ironmongers, decided to retire because they could no longer find workers interested in learning this art.

It seemed that the youth of that age preferred employment in modern businesses where they could make fast fortunes – or so they hoped – rather than toil as apprentices for years in a sweaty-hot trade for little pay.

An earlier generation of Mangins, L to R: Francois Able Mangin (1833- 1915, born at sea during September 1833 voyage to America aboard the Tamerlane. Died in New Orleans), Charles Antoint Mangin (1822-1869, born in Remiremont, France, died in New Orleans) and Eugene Mangin (1830 - 1869, born in Remiremont, France, died in New Orleans). Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

Jean Able Mangin. Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

Charles A. Mangin, Jr. Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

Each wrought iron piece from the brothers’ shop was unique and original. Just as they retired, Times Picayune reporter Marguerite Samuels published an interview with Charles Mangin in which the smithy explained his theory of the French Quarter’s iron decorations:

Wrought iron is like an oil painting – every stroke is put on by hand, and there is only one copy in the world. Cast iron is like printing – once you have the plate, you may run off millions of copies.

Inside Jean Able Mangin’s workshop, at 502 Chartres Street, 1902. Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

Cast iron was less expensive and easier to produce in quantity than wrought iron. While the Mangin brothers produced both types in the shop, they considered cast iron less lovely, less artful. A result of mass production.

The Mangins’ grandfather, Jean Antoine Mangin, arrived from France in 1832 and set up his shop at 621-623 Bourbon Street. In the courtyard stood a red-hot forge with a massive bellows, surrounded by blackened tools, scattered bits of ironwork and the smells of a coke fire.

621-623 Bourbon Street, circa 1885. Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

621-623 Bourbon Street, November 2023. The building was the also the home of Congresswoman Lindy Boggs from 1972 until Hurricane Katrina in 2005. She sold it in 2011. Photo by Ellis Anderson

Detailing on the canopy above the upstairs balcony of 621-623 Bourbon Street. The supports are wrought iron, while most of the decorative work on the canopy is cast. The Mangins created both wrought and cast iron work. It’s unclear if they created the work on this building or if it existed when they purchased it.

Wrought iron supports at 621-623 Bourbon

At least, it did stand there until the Mangins’ retirement eighty-eight years later.

Of his apprenticeship with his family, Charles said the crafting of iron had come naturally to him.

I had hardly to learn at all. It was born in me. I have worked around a forge since I was fourteen. Every member of my family has been an ornamental ironworker, except one, the smartest – he was a priest.

The wrought iron ornamentation of 621 and 623 Bourbon is among the most graceful in the French Quarter, and each piece of the arrow-style design was made by hand on that forge. A photograph from 1885 shows Charles and Jean with their crew standing before this address, surrounded by the products of their trade.

An 1885 photograph of the Mangins and crew in front of their Bourbon Street workshop. Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

A bill from 1879, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

Ironwork that issued from their forge is scattered throughout the city. Another arrow-design balcony graces 837 Royal Street at Dumaine. That work was produced by Charles and Jean’s uncle, probably François Able Mangin, prior to 1915.

The father of the Mangin brothers, Charles A. Mangin, Sr. (1822-1869), apprenticed under the smith who decorated the extraordinary Gauche House at 1315 Royal Street, as that home was built.

The Gauche House at 704 Esplanade and 1315 Royal. Charles Mangin, Sr. apprenticed under the smith who decorated this home.

Detail from the Gauche House

Detail from the Gauche House

And the Mangin tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, where most of Famille Mangin rests, is surrounded by a fine fence that was born from the fires at 621 Bourbon.

Charles Mangin kept within his shop a collection of ironwork from lost New Orleans homes and businesses. Even then, developers were destroying the city’s history to build newer structures.

He loved the French-made balcony next door at 619 Bourbon, and believed it to be the oldest in the city. But he considered the works gracing the façade of Waldhorn’s Antiques Shop at 343 Royal Street to be the most beautiful.

It has the French brass ball at the end of a scroll-design which could not have been made in less than eight heats for every scroll. And the scroll is repeated an uncountable number of times.

Waldorn’s Antiques, circa 1880 - 1910, by Morgan Whitney, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

Detail of ironwork at 343 Royal today, photo by Ellis Anderson

Although etymologists might disagree with him, Charles claimed to know the origin of the word veranda:

A certain hidalgo of Spain, by the name of La Veranda, with an open gallery outside his house, had a sudden architectural inspiration to protect his family against sun and rain. He ran up pilasters, and put on a roof – and behold! the snuggest balcony Saville had ever seen. Delighted, his daughter never left the spot. She was a striking beauty, with Castilian coloring and a lift to her head that made passersby say, “Look! That’s La Veranda.”

After the shop shuttered in 1920, the brothers remained close, though they went their separate ways – perhaps for the first time in their lives. They rented out the storefront at 621 Bourbon, which became a massage parlor (no, not that kind). In the 1930s it was home to a business called National Chemical Company. Today it’s a souvenir shop.

Charles and his longtime wife Antonia moved into 623 Bourbon, where they remained until Charles’ death in 1924 at the age of 70.

Charles and Antonia Mangin in later years. Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

Photo courtesy Roy Arrigo, the great-grandson of Jean Mangin.

Jean moved to Royal Street for a few years, and then uptown to 1455 S. Galvez Street, where an original iron chandelier from one of the Pontalba Buildings hung from the ceiling. He continued some work, but mostly he made keys, notably for the Pontalbas and for St. Louis Cathedral.

Jean advertised his trade with an anvil and a giant key balanced atop it, that stood outside his shop at the Royal Street location. “The anvil that is in the Cabildo was his anvil,” said Roy Arrigo, great grandson of Jean Mangin. “It was actually a blacksmith's sign, much the same as back in the days when most of the population couldn't read.”

Jean retired even from the key-making business in the early 1940s. “The keys of the cathedral were stolen not long ago,” Jean told a reporter in 1943. “But when Father came to ask if I could make another set, I had to say no. I can’t see.”

Jean passed away in 1948 at the age of 89, the last in the line of the French Quarter forgerons.

A Mangin Brothers signature plate on a simple Dauphine Street gate. If you know of more Mangin Brothers plates, please email us. Photo by Ellis Anderson

References: Marguerite Samuels, “Art in the Iron Verandas of New Orleans: Last of the Forgerons Closes His Shop Here,” Times-Picayune, June 6, 1920, sec. 3, p. 1.Frances Bryson, “Holds the Key to Iron Work Here with Long Achievement Record,” New Orleans Item, August 20, 1943. The author extends special thanks to Roy Arrigo, great-grandson of Jean Able Mangin, for information and photographs.

Love our French Quarter coverage?

We can't do it without you!

Become a member of our Readers’ Circle now: