Southern Decadence: the Origin, Traditions – and, of course – the Parade

Photo of the 2023 Southern Decadence Parade by Melanie Cole for French Quarter Journal. See the complete 2023 album here.

August 2024While more than 250,000 people flock to the annual LGBTQ+ French Quarter celebration on Labor Day weekend each year, few are aware of the event’s half-century history and its Sunday parading tradition.

- by Frank Perez

These are the dog days of summer. The heat is insufferable. The humidity, oppressive. Ennui hangs in the sticky air. Every step out of doors is a study in sluggishness. Indolence and lethargy rule the day. Summer in New Orleans.

These were the conditions that gave rise to a small house party in 1972. The invitation read, “Ya’ll Come to the dress up as your favorite Southern Decadent—Party at Belle Reve, 2110 Barracks, late afternoon, Sunday, September 3.”

First Southern Decadence party invitation, designed by Robert Laurent in 1972

The host? A group of close friends who dubbed themselves “The Decadents.” The place? A run-down home in the Treme neighborhood owned by David Randolph and his lover Michael Evers. The place had become a headquarters of sorts for the Decadents.

Robert Laurent remembers noting the decay of the home: “Why, it’s like the faded and withered spirit of Blanche Dubois’s Belle Reve from A Streetcar Named Desire.” The name stuck. The guests: about 50 friends and acquaintances.

Randolph was not there. He had left town because of a family emergency, an emergency that would keep him in Michigan and eventually require Evers to leave New Orleans to join him. So, two weeks later, on Saturday, September 16, another party was held, this one a going away party for Michael Evers. The invitation, again designed by Laurent, read, “Come back to Belle Reve.”

The second Southern Decadence party invitation, designed by Robert Laurent, 1972

Thus, the birth of Southern Decadence. From these humble origins, Southern Decadence gradually grew but, for the most part, at least until the mid to late 1990s, it was, primarily, a local affair—and that only for locals in the know.

If you lived in the Quarter, you probably knew a bunch of bearded men in dresses and their friends in makeshift costumes would drink their way around the neighborhood on the Sunday before Labor Day.

In 1973, Laurent suggested they have another party, but that everyone gather at Mattassa’s Bar (behind the neighborhood grocery which still exists). From there the Decadents could “parade” back to Belle Reve.

It was a popular idea, and they did it again in 1974 – only this time, they selected a Grand Marshal to lead the parade. The honor went to the late Frederick Wright, a friend of Laurent’s and one of the fellow “Decadents.”

In Southern Decadence in New Orleans, Maureen Block remembers, “Frederick simply had to be the first grand marshal. There was no question about it.” Though he did not live in the city, “he would always make time for a stopover in New Orleans for his job travels …

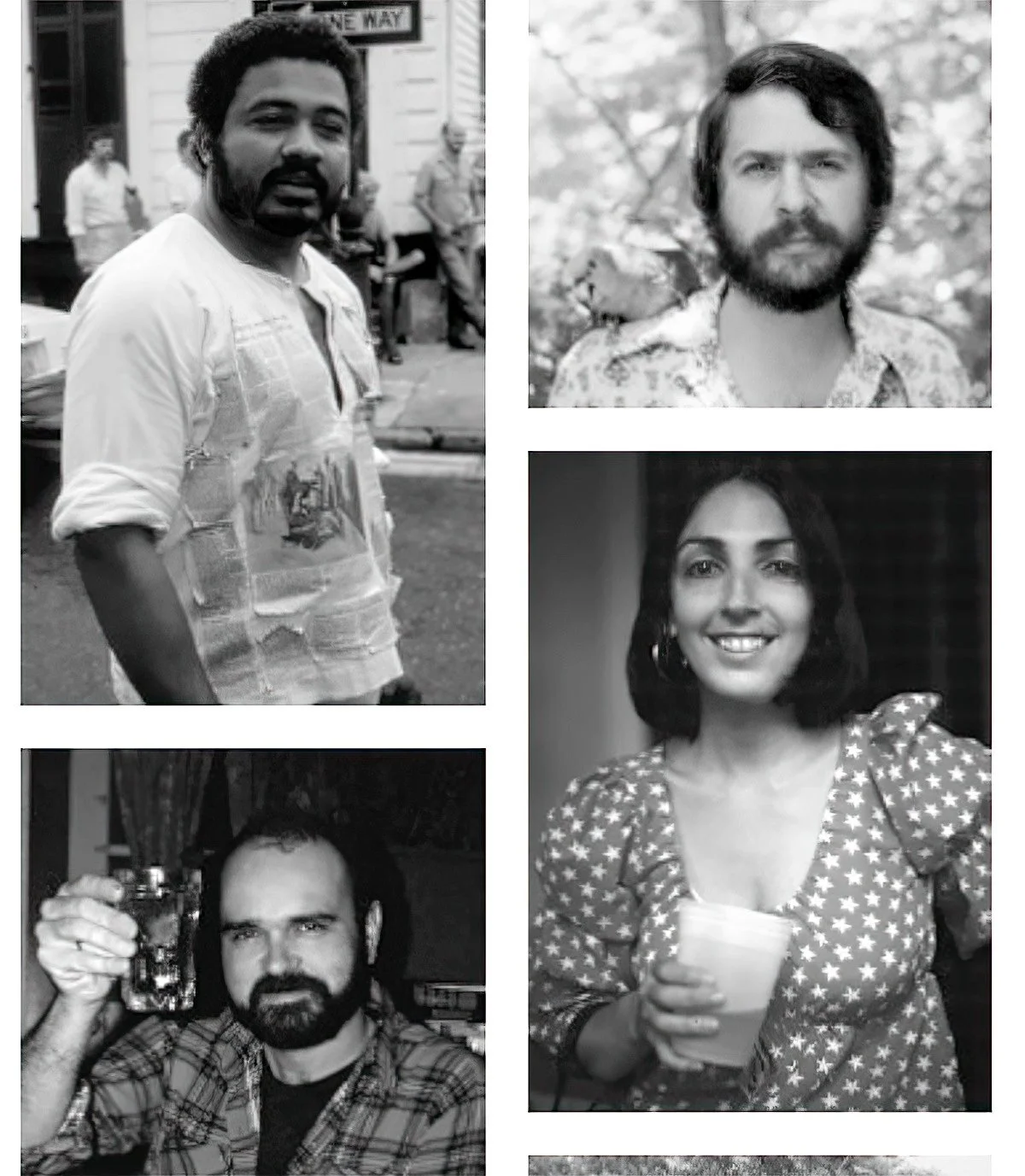

The founders of Southern Decadence, clockwise from top left: Frederick Wright, Robert Laurent, Maureen Block, and Michael Evers

“Everyone fought to pick him up at the airport. He was the guiding spirit of the group, a natural force. No one knew what he’d do next, the life of the party, but with a huge heart. Just a lovely man.”

Wright, a gay Black man, led the parade dressed as Uncle Sam. Southern Decadence has always been subversive, even without intending to be.

By 1980, the focus had shifted from the house party to the parade. Even in the 1980s, the parade was nothing like it is now. Then it was more of an informal bar crawl. The first parade permit was not issued until 1997.

After the advent of the internet in the 1990s, Southern Decadence grew exponentially in both participants and visitors, as well as in terms of economic impact, typically over $300 million annually. Over 250,000 revelers are expected to attend Southern Decadence 2024. The parade on Sunday is projected to have at least 34 marching groups and 2,000 participants.

Photo of the 2023 Southern Decadence Parade by Melanie Cole for French Quarter Journal. See the complete 2023 album here.

Photo of the 2023 Southern Decadence Parade by Melanie Cole for French Quarter Journal. See the complete 2023 album here.

In the early years, the parade did not have an official route; rather, it meandered around the Quarter at the whim of the Grand Marshal. This spontaneity was a source of much of the parade’s energy and created some unforgettable moments over the years.

For example, in 1986, Grand Marshal XIV Kathleen Conlon led the parade to the Riverwalk on its opening weekend where several drunken revelers jumped in the park fountains, much to the amusement and astonishment of throngs of tourists.

But 1980 marked a turning point for Southern Decadence. That year, the parade was hijacked by a marching band. Grand Marshal Tom Tippin led the parade from Mattassa’s to Jackson Square and wanted to go up Decatur to hit the Greek sailor bars, but a band marching in the parade—the Pair-A-Dice-Tumblers—wanted to go downriver to Frenchmen Street. The crowd followed the band and Tippin was furious.

In Southern Decadence in New Orleans, Preston Hemmings remembers watching “in disbelief as the band took off in one direction and the parade marshal in the other. Since the band was going where they wanted to go, naturally the whole parade, with few exceptions, went that way. Decadence, on that very spot, as we had known it, died… We were all just in shock.”

Throughout the 1970s, the Grand Marshal was selected basically by group consensus among the founders, but that changed in 1981. By then, the founders were getting older and moving on with their lives. In addition, the bar at Matassa’s closed and the parade would now start at the Golden Lantern, previously its ending point.

Also, the reigning Grand Marshal would now have sole authority to select his or her successor(s). Neither qualifications nor criteria for being Grand Marshal have ever been established. All that was – and is – required is that the would-be Grand Marshal be in the good graces of the reigning Grand Marshal. There has never been a nomination or application process.

The practice of the reigning Grand Marshal(s) selecting whomever he/she/ they desire builds excitement and anticipation which culminates at the official announcement party – usually held right after Easter. In the days leading up to the announcement, gay barflies are abuzz with speculation as to who will be named. Some years it’s easy to guess; other years it’s not. Some designees are a complete surprise, others are fairly predictable.

Former Grand Marshals at the Gay Appreciation Awards in 2021, courtesy Ambush Magazine

Click here to access a list of all Southern Decadence Grand MarshalsAll this history is lost, of course, on the 250,000+ out-of-town revelers who come each year to New Orleans for Labor Day weekend. Southern Decadence has certainly outgrown the parade at its nucleus.

Many out-of-town revelers probably don’t even know there is a parade. Nor are they familiar with the tradition of Grand Marshals. They’re here to party, and that’s great.

Local business owners, especially gay bar owners, love Southern Decadence because of the financial bonanza it brings. Yet, business owners are divided on the tradition of the Grand Marshal’s Walking Parade.

One owner recently told me he wished there would be no parade and no Grand Marshals. Another remarked, “No one knows or gives a damn who the Grand Marshal is.”

Other LGBTQ+ community leaders point out that Southern Decadence, at its fundamental core, is a celebration of friendship. It was never intended to be an opportunity for businesses to make money.

Some also maintain that without the Grand Marshals and their walking parade, Southern Decadence would be just another circuit party that could be held anywhere in any city. And the celebration is one of the things that makes New Orleans’ LGBT+ history and community distinctive.

Photo of the 2023 Southern Decadence Parade by Melanie Cole for French Quarter Journal. See the complete 2023 album here.

Photo of the 2023 Southern Decadence Parade by Melanie Cole for French Quarter Journal. See the complete 2023 album here.

Southern Decadence has come to mean different things to different people. To purists, it’s the traditional Sunday parade. To bartenders and servers, it’s a mortgage payment or car note. For Billy Bear from Atlanta, it’s a chance to get away from the office and cut loose.

For the closeted and uninitiated, it’s a baptism by fire. For religious zealots, it’s an opportunity to condemn. For local allied businesses, it’s a bump in slow summer sales. And for Quarterites and other locals, it’s a sacred tradition that cannot be duplicated anywhere else.

While some of the original Decadents have passed away, several are still around. If you look carefully at the beginning of the parade – outside the Golden Lantern as the Grand Marshals make their toasts and prepare to blow their whistles – at the edge of the gathered crowd you might spot a few “old-timers” in lawn chairs, beholding the spectacle about to unfold.

These are the original Decadents—Robert Laurent, Charlie and Maureen Block, Tom Tippin, and Will Hemmings. They do not wish to speak, nor do they want to be recognized.

Rather, they prefer to watch in solemn amazement and think to themselves, “My God! What have we wrought?”

In 2018, the LGBT+ Archives Project of Louisiana honored the founders of Southern Decadence for donating a wealth of archival material to the Louisiana Research Collection. This photo of SDGMS features Tom Tippin (seated in the center) with Robert Laurent behind him and Kathleen Kavanaugh next to him. Photo courtesy Frank Perez

Perez, Frank and Smith, Howard P., Southern Decadence in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2018. See your local independent bookseller or click here to order from LSU Press.

Your support makes stories like this one possible –please join our Readers’ Circle today!