Revisiting the Civil Rights Movement in “The Trail They Blazed”

Panels in the new “The Trails They Blazed” traveling exhibit, currently on display at the TEP Center.

October 2023A new traveling exhibit, currently at the TEP Center through November 12th, brings on both memories and reflections for a New Orleans writer.

– by Juyanne James

– photos by Melanie ColeI have always been mesmerized by the Civil Rights Movement. Too young to participate in Freedom Rides, sit-ins, or the March on New Orleans’ City Hall, I was nowhere near old enough to fight for voter rights or to boycott Canal Street. And yet, I do remember that years later, our Black school in rural Louisiana was closed and shuttered like a dream, before we were sent to the nearby white school.

As with most people, the Civil Rights Era has remained with me, through readings and experiences I lived or heard about, or events I took part in over the years. One of those events happened recently, on September 16, when I was invited to an educator’s viewing of a new and important exhibit appropriately titled “The Trail They Blazed.”

The exhibit has been produced by The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC), through NOLA Resistance: The Civil Rights Movement in New Orleans – using a grant from the National Park Service. THNOC plans to share the traveling exhibit with local businesses, schools, colleges and religious institutions over the next two years.

“The Trail They Blazed” offers audio interviews[1] with local civil rights icons, including Sybil Haydel Morial, Leona Tate, Malik Rahim, Doratha “Dodie” Smith-Simmons, Dr. Ralph Cassimere, Don Hubbard, and Katrena Ndang. The exhibit will remain on display until November 12 at the TEP Center, 5909 St. Claude Avenue.

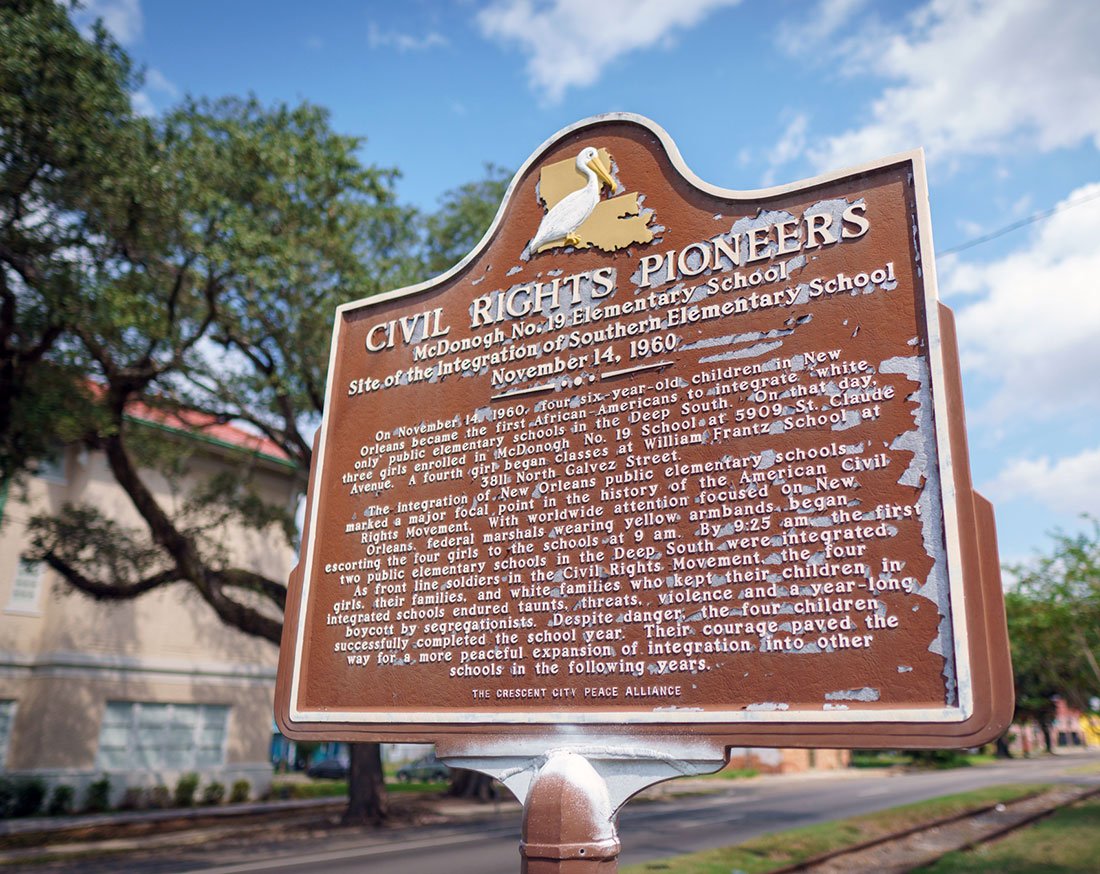

This address may sound familiar. It is formerly McDonogh #19 Elementary, the Lower Ninth Ward school that was desegregated on November 14, 1960, by the three first grade girls who would come to be known as the McDonogh Three: Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, and Tessie Prevost. Many people also connect that memorable day to Ruby Bridges, who desegregated William Frantz Elementary.

The TEP Center, formerly McDonogh #19

Before I attended the educators’ event to see the exhibit, I learned that the Leona Tate Foundation for Change was part of a two-year restoration of the McDonogh 19 building, which had lain dormant since 2004 when the school was closed and subsequently damaged by Hurricane Katrina. The former school has now been renamed the TEP Center – representing the last names of the three girls: Tate, Etienne, and Prevost.

Tate’s foundation now partners with The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond (PISAB) and another organization, the Beloved Community, to offer innovative “Undoing Racism” education programs across the country. Although the TEP Center has transformed the school into a center with its main focus on fighting structural racism, the top floors of the building also offer affordable housing to seniors.

On the Saturday morning of the event (September 30), I felt a real excitement. As I dressed to attend the exhibit, happily ironing my favorite black pants and a summer blouse, I couldn’t help but reflect on how important the TEP Center’s goal is. Leona Tate has said, “I’ve been ready and remain committed to fighting racism since my first day at McDonogh 19, a building I now co-own. There is power in that.”[2]

There certainly is. When I think about “the world we live in,” as it is often said, I wonder if racism will ever be eradicated, and seeing Tate and her foundation take on this challenge simply warms my heart. The fact that she began her fight against racism at McDonogh 19 all those years ago, as a child, seems to strengthen her resolve to carry on the fight today.

A panel about the mission of the TEP center with The McDonogh Three, Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, and Tessie Prevost.

I also reflected on my own past. While I had not been at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement, most likely my parents, my aunts and uncles, and my entire community had watched and witnessed the world changing. At that point, neither of my parents had finished high school because both were tasked with working in the fields, helping to take care of their families.

And yet, my mother loved the idea of learning. I am almost sure that she watched in horror and disappointment as the McDonogh Three were yelled at, spat at, and called every name other than their own. She would have hated to see those girls threatened so and would have said a prayer for them and their families. She likely pulled the few children she had at the time (she would eventually have eleven) closer to her bosom, saying something like, “Dear, heavenly Father…”

I am sure she internalized what was happening and felt her own sense of fear. Her kind, kind heart must have been breaking; she always hated knowing that humans are capable of doing the most atrocious things to each other.

I put away my thoughts, though, and traveled to the Ninth Ward. I marveled that things are still not “back to” pre-Katrina levels—so many homeless slabs, broken buildings, missing businesses and people—but as I bounced over the canal and pulled up to the new TEP Center, the old McDonogh 19, I would soon learn that the Ninth Ward was the only part of New Orleans to take part in the integration of schools on that day in 1960, and only then because it was “a low-income area.”[3]

I parked and walked into the beautifully restored building. The place felt fresh and old: fresh with new ideas and old with memories. The exhibit greeted me—panel after panel, story after story, photo after photo, of those local Civil Rights icons so visible. I saw the likenesses of the three girls first, but the other faces and voices of the project as well.

Almost immediately, I saw Leona Tate moving here and there, through the panels, taking care of last minute details. She looked regal, still beloved and admired for all she must have sacrificed. In a beautiful yellow dress, she seemed the embodiment of hope; the color also seemed symbolic of the yellow armbands the Marshalls wore back then, to set them off and label them as protectors of the McDonogh Three.

Leona Tate

Someone introduced me to Tate, but I was tongue-tied with admiration. I wanted to ask her how she felt on that particular day, all these years later, especially as a participant in this inaugural exhibit of the NOLA Resistance Oral Project. Actually, she looked quite responsible, as the person reviving the McDonogh building, renaming it, and assigning it the task of fighting a very old and lasting foe: racism. I did manage to say, “Hello,” before she rushed to another chore.

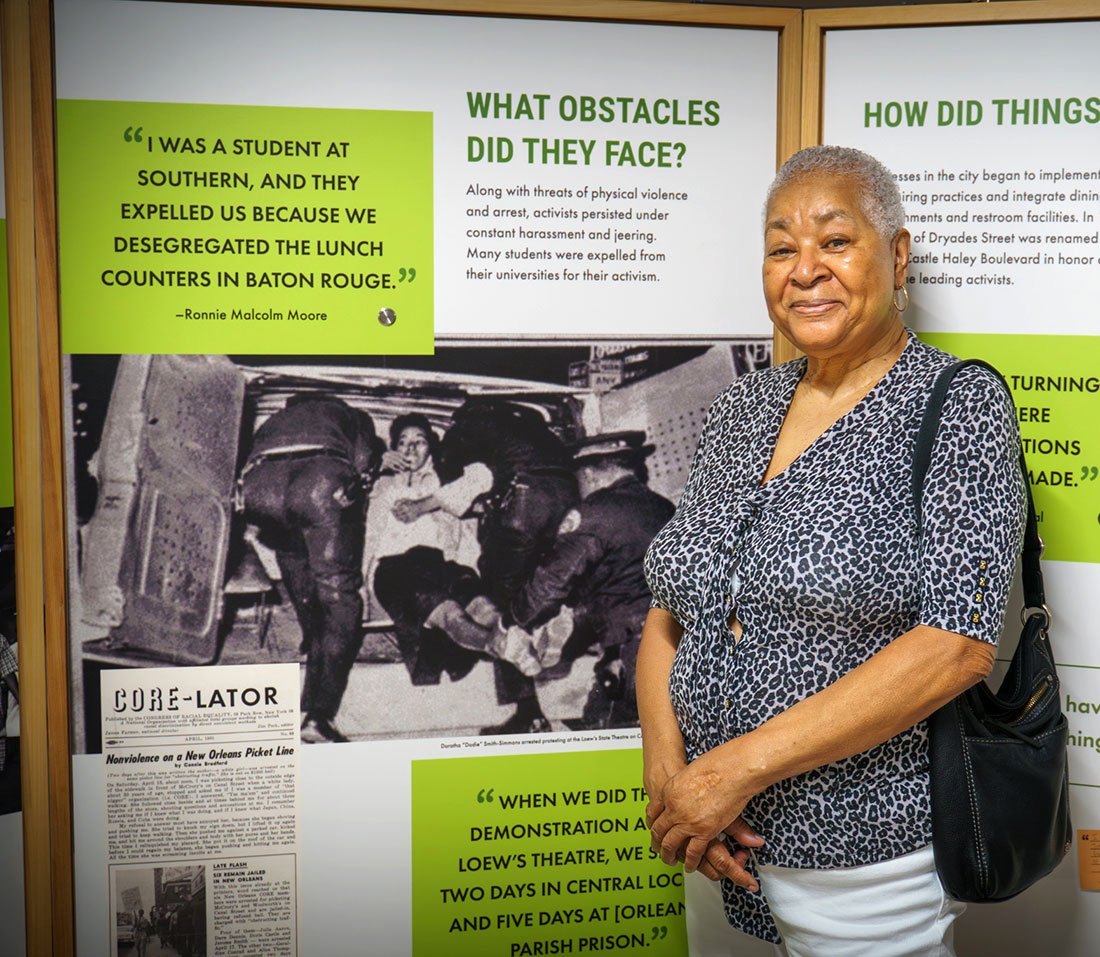

I returned to the panels and began to read the storyboards and listen to the recorded voices of the civil rights icons. I was reminded that the Freedom Riders were mainly fighting for the enforcement of the federal ruling to provide integrated facilities for interstate travel, as well as fighting against segregation on public buses. Dodie Smith-Simmons was one of the “test riders” sent out before the national Freedom Rides began; she talks about a stop in McComb, Mississippi, at a Greyhound bus terminal, where she and other Freedom Riders barely escaped with their lives.[4]

Doratha "Dodie" Smith Simmons by a panel showing a photo of her younger self.

Doratha "Dodie" Smith Simmons with her goddaughter

Dr. Ralph Cassimere, Jr. and Katrena Ndang talk about voter registration and how blacks were often prevented from registering based on almost impossible requirements. Dr. Cassimere poignantly speaks of his grandmother who was 75-years-old when she was finally able to register to vote.[5]

And yet, there are few things as resonant as listening to Leona Tate’s memories of that day: her mother’s instructions to not put her “face to the window”; the many people on horseback; how she thought all the people on the street meant it was a Mardi Gras parade; how the girls could not go outside or look out the windows that entire year; how they would later go to TJ Semmes Elementary, without the protection of the U.S. Marshalls.[6]

In the background, while I walked and read and listened to the exhibit, the great trumpeter Gregg Stafford and his ensemble played Preservation Hall favorites. I was reminded that music was an integral part of the Civil Rights Movement. Smith-Simmons says they opened each CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) meeting by crossing their arms, holding hands, and singing, “We Shall Overcome.” She also says that when they were arrested and thrown into jail cells, singing became a pastime late into the night.[7]

Gregg Stafford and the Young Jazz Hounds

I smiled and smiled, so joyous to bump into one legend after another. Sybil Haydel Morial looked as important as she always does, lovingly flanked by a couple of her children. Malik Rahim, in locks aged by time, looked every bit as militant and as sure as ever. Dodie Smith-Simmons stood close by the Freedom Rides panel, surrounded by family but looking as brave and as focused as ever. Don Hubbard, when he walked up to the March on City Hall panel, marveled at how young he looked back then.

L to R: Oral historian Mark Cave and activist Don Hubbard

I wanted to tell them all that they were still beautiful—back then their beauty came with their strength and courage, with their actions; but now, just because they are still here, still fighting and standing up for justice. I had always imagined that these civil rights legends knew something that the rest of us did not. How could they not? How can we ever understand the type of courage it took for them to risk their lives, their dignity, their individuality—to walk into those classrooms day after day, to walk those streets holding up picket signs into the night, to step on those buses, not knowing if they would make it home again.

Activist Malik Rahim

I also wonder if there was anything as important as what was happening on that Monday morning, in November 1960. Yes, our 35th president, John F. Kennedy, was elected that same month. Yes, Cassius Clay (who had not yet changed his name to Muhammed Ali but who had won a Gold medal at the Olympics in Rome that year) had just fought his first professional fight in October of that year. Yes, American soldiers were being sent to fight in Vietnam.

And yes, the Civil Rights Act of 1960 had been passed, to strengthen loopholes left by the Civil Rights Act of 1957, thereby attacking voter disenfranchisement. These things and more must have alerted everyone’s consciences; and yet, here, in New Orleans, and soon for the rest of the world, November 14 became a day that could and would change racial history in America.

As more and more people ushered in to see the inaugural moments of the exhibit, The Historic New Orleans Collection sponsors and the TEP Center founders gathered to welcome everyone. They thanked all the civil rights legends for being a part of the project. They thanked all those who put in time and effort to make sure the exhibit is sound and can travel to every appointed stop. They thanked everyone for coming, for being witnesses to such an important event. They reminded us of the importance of the local civil rights efforts, which remains vitally important to the history of the Civil Rights Movement. The world was watching all those years ago, just as they are watching now, and this exhibit proudly represents New Orleans’ civil rights journey.

L to R: Kathe Hambrick, executive director of the Amistad Research Center, Doratha "Dodie" Smith Simmons, Daniel Hammer, THNOC president and CEO.

L to R: Eric Seiferth, THNOC curator of the exhibition and activist Malik Rahim

Doratha "Dodie" Smith Simmons with THNOC's Heather Hodges, right, Director of External and Internal Relations

As I left the building that day, the civil rights stories sat heavily on my heart. Mostly, I thought about the violence that must have been enacted against those little girls. I see six-year-olds today, and I understand how much strength Leona, Gail, Tessie, and Ruby must have all those years ago. I think of myself at that age, and our school was not integrated. At six years old, I had few cares in the world; I spent my days in laughter and quiet learning. I did not witness hatred being flung in my face each day as I walked into school. I did not fear, even once, or wonder that I might be harmed. I was simply allowed to be a child.

If this traveling exhibit, “The Trail They Blazed,” does nothing more than remind the world that there was a time in our history when six-year-olds could be hated so vehemently, as well as have that hatred acted upon them so openly, then the efforts of THNOC and these great civil rights leaders will be a success.

My prayer, much like my mother’s must have been on that day in November 1960, is that we learn how to treat each other better. Getting rid of structured racism is a perfect start.

NOLA Resistance Oral History Project offers full audio and transcripts of interviewees, as well as lesson plans based on the oral histories.

[1] NOLA Resistance Oral History Project, hnoc.org/research/nola-resistance-oral-history-project#school-integration

[2] Leona Tate, Founder/Executive Director, TEP Center, “Commitment to Anti-Racism,” https://www.tepcenter.org/ commitment-to-antiracism

[3] Leona Tate Interview, NOLA Resistance Oral History Project: Public School Integration, hnoc.org/research/nola-resistance-oral-history-project#school-integration

[4] Dodie Smith-Simmons Interview, NOLA Resistance Oral History Project: The Freedom Rides, hnoc.org/research/ nola-resistance-oral-history-project#school-integration

[5] Dr. Ralph Cassimere, Jr. Interview, NOLA Resistance Oral History Project: Voter Registration, hnoc.org/research/ nola-resistance-oral-history-project#school-integration

[6] Leona Tate Interview, NOLA Resistance Oral History Project: Public School Integration, hnoc.org/research/nola-resistance-oral-history-project#school-integration

[7] “We shall overcome; we shall overcome; we shall overcome, some day. Within my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome some day,” Inspirational song of freedom, public domain, 2018.

Join our Readers’ Circle now!