The Arberesh Community in New Orleans - Part One

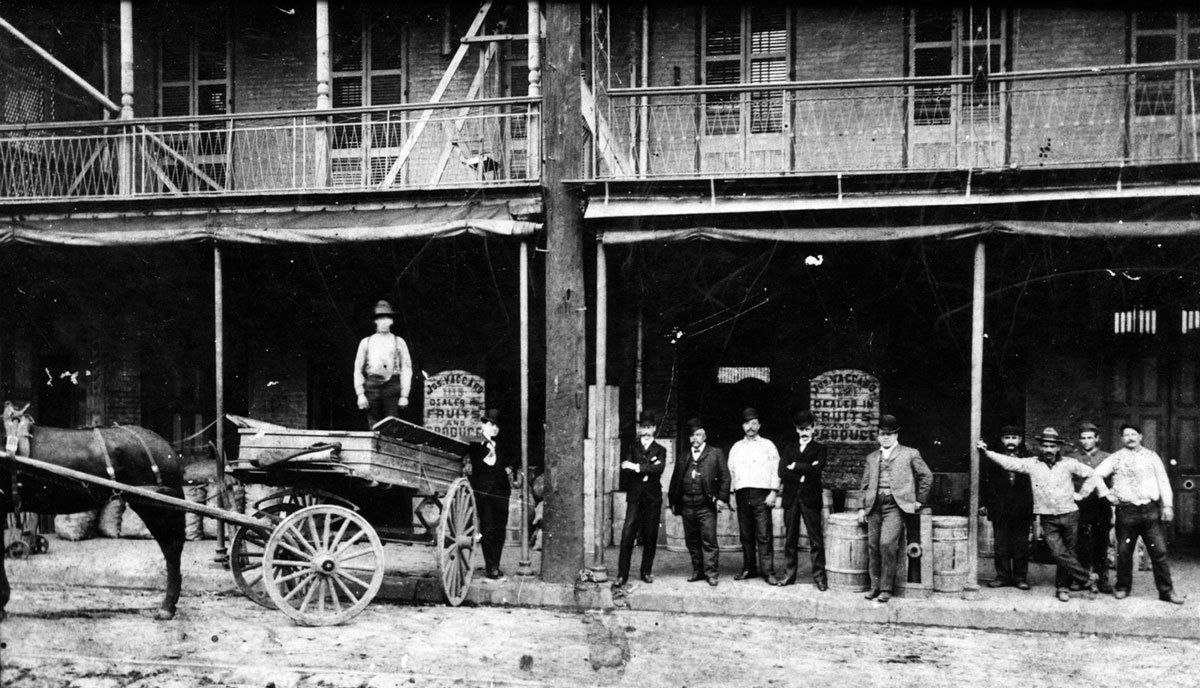

Joseph Vaccaro Fruit and Produce at Poydras and Baronne Streets, 1897. The family is one of many in New Orleans who have Arberesh roots. Photo from the The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.325.3982

November 2024From Albania to Sicily to New Orleans: across two continents, three countries, and five centuries, some members of the city’s Arberesh community still honor their roots, while others are just discovering them.

– by Mark Orfila

This column is underwritten in party by Jeannette Bolte, PhD

This is the story of an Albanian feudal chieftain who defended his homeland against overwhelming odds. It’s also about the Hotel Monteleone. And Lucky Dogs. And tens of thousands of modern day New Orleanians who may be utterly unaware of a fascinating aspect of their own heritage.

The story starts 500 years ago and 5,000 miles from the French Quarter, but for now let’s jump in with the luxurious hotel and the streetside seller of wieners. These two iconic French Quarter institutions couldn’t be more different, yet they have one thing in common. Antonio Monteleone, the cobbler-turned-hotelier who founded the hotel in 1886, was an Arberesh immigrant. So were the forefathers of Stephen and Erasmus Loyacano, the brothers who founded the Lucky Dog company in 1947.

A photo of Antonio Monteleone in the book Shqiptarët e Amerikës (The Albanians of America) by Vehbi Bajrami by Vehbi Bajrami. The Albanian caption reads “Antonio Monteleone, founder of the Monteleone Hotel in New Orleans in 1886.”

1927 photo print of the Hotel Monteleone, photo Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Eleanor G. Burke, 2012.0328.6

Lucky Dog vendor in 1976, on Iberville between Bourbon and Dauphine. Photo by Josephine Sacabo, The Historic New Orleans Collection,1976.128.12

Among the cultural layers that created today’s French Quarter – Chitimacha and Choctaw, French and Spanish, Senegambian and Congolese, Haitian and Cuban, Italian and Sicilian, Chinese and Vietnamese – the Arberesh don’t get mentioned much. In much the same way that Cajuns can trace their ancestry through Canada back to France, following the Arberesh family tree to its roots takes you through Italy and across the Adriatic to Albania.

The Arberesh, who began emigrating here in the mid 1800s, had lived in Sicily for generations – but always within their own semi-autonomous ethnic enclaves. Their mother-tongue was an archaic dialect of Albanian, unrelated to Italian. They practiced their own version of Catholicism – Byzantine rather than Roman. Even their physical features set them apart to some extent. Among some of the Arberesh living in Sicily, intermarriage with “Latins” invited ostracism.

But in the melting pot of America, it was inevitable that these boundaries would be blurred. Bret Clesi, who has done extensive research into his Arberesh heritage, estimates that there may be as many as 100,000 of his fellow Louisianians who share some part his Arberesh DNA.

While the vast majority of these “cousins” of Clesi’s probably have at least some awareness of their “Sicilian” or “Italian” ancestry, it is doubtful that more than a handful have ever heard the word “Arberesh.”

Bret Clesi in his CBD office, surrounded by all things Arberesh, photo by Ellis Anderson

Charles Marsala, who will be representing the Italian side as grand marshall in the Louisiana Irish-Italian parade next spring, is a case in point. His forebears on both sides came from Sicily. He grew up immersed in Italian-American culture and is intensely proud of his Italian heritage. His grandfather, Charles Vincent Marsala Sr., was instrumental in founding the American-Italian Federation of the Southeast.

Five years ago, at the age of 59, Marsala was selected as the president of that very organization. That was when he first learned that that same grandfather was actually Arberesh. The younger Marsala enthusiastically embraced this newfound aspect of his cultural identity. In 2022 he journeyed to Sicily and Albania, both of which have now become central to his sense of ancestral homeland.

Clesi discovered his Arberesh background much earlier in life. He was about ten years old, and he remembers vividly how it happened: His grandfather was taking him to Central Grocery for a muffuletta. Pausing outside, Mr. Clesi paused to prepare young Bret for what he was about to witness.

“The guy working in there is going to shout something at me in Italian, and I’m going to reply to him in Albanian. And it might sound like we’re angry, but don’t worry – we’re not being mean. It’s just the way we greet one another.”

The scene played out just as predicted. When Mr. Tusa spotted Mr. Clesi walking in the door, he shouted out from behind the counter, “Hey, Gheg-Gheg!” and Mr. Clesi shouted back, “Hey Liti!” Despite his grandfather’s advance warning, Bret found the whole exchange a little confusing and disturbing.

Later, Mr. Clesi referenced the incident to teach young Bret about his own heritage. The Tusas were originally Sicilian, and the Clesis were originally Albanian, he explained. Mr. Tusa and Bret’s grandfather were acknowledging their unique backgrounds in a teasing way:

Hey Albanian!

Hey Latin!

This childhood incident launched Clesi on a lifetime dedicated to discovering his heritage. A passionate amateur anthropologist and historian, Clesi has fashioned himself as one of America’s foremost authorities on all things Arberesh.

Like Marsala, he has made pilgrimages to both Sicily and Albania. In 1996, the president of Albania named him the Honorary Consul-General of the Republic of Albania. Since then, his diplomatic colleagues have elected him to two consecutive terms as the dean of the Consular Corps of New Orleans.

Bret Clesi pointing out details in the book Shqiptarët e Amerikës (The Albanians of America )– by Vehbi Bajrami

Marsala and Clesi can readily reel off a long list of entrepreneurs and innovators, like the Monteleones and Loyacanos, who helped shape the French Quarter and the city as a whole.

For instance, there are the Vaccaro brothers who founded the Standard Fruit Company, the predecessor of today’s multinational giant, Dole. And the baker Lawrence Aiavolasiti, known affectionately as “Mister Wedding Cake.”

And we mustn’t forget the King of Crawfish, Al Scramuzza, who made local news recently when Metairie marked his 97th birthday by naming a street in his honor. New Orleanians of a certain age will remember his over-the-top tv ads for Seafood City, which he later adapted as a campaign slogan when he ran for political office in 1983: Vote for Al Scramuzza, and you’ll never be a loser.

Speaking of politics, Victor Schiro, whose two terms as mayor of New Orleans encompassed most of the 1960s, was also Arberesh. It was during the Schiro administration that the New Orleans Saints franchise was founded and the vision for the Superdome first articulated.

Victor H. Schiro (1904 - 1992), New Orleans mayor 1961 - 1970. Photo Historic New Orleans Collection, 1978.177

In a city world-famous for its food, the Arberesh community made their share of culinary contributions. Granted, not every foodie would be inclined to include the Loyacano brothers’ famous French Quarter franks on a list of “culinary contributions.” But what about Frank Manale, who opened Pascal’s Manale in 1913, the birthplace of the dish New Orleans knows as “barbecue shrimp?”

And before that, Anthony Tortorich, whose restaurant opened at the beginning of the 20th century just two blocks down Royal from the Monteleone. Tortorici’s would endure more than a hundred years, earning the title of New Orleans’ oldest Italian restaurant before finally becoming a Katrina casualty.

The site of Tortorici’s Restaurant, circa 1934 - 44, The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1977.264

Although the restaurant closed during the pandemic and another one operates in the building now, this sign still remains. Photo by Ellis Anderson

Then there was Marti Shambra. His restaurant, which opened in 1971 at the corner of Rampart and Dumaine, was an early pioneer of the whole bistro concept in New Orleans and ultimately gained a reputation as one of the neighborhood’s most prominent gay-friendly establishments – as well as a favorite hangout of Tennessee Williams.

The fabled Marti’s Restaurant on the corner of North Rampart and Dumaine Streets. It was one of Tennessee Williams’ favorites – his last French Quarter home was located at 1014 Dumaine Street. Historic New Orleans Collection, 1991.1.1

If you challenge people like Marsala and Clesi to define what makes them proud of their heritage, they may mention these names and more. But they will invariably invoke the name of that aforementioned Albanian feudal chieftain - Gjergj Kastrioti, aka Skenderbeg.

Skenderbeg’s greatness was acknowledged by both friend and foe in the 15th century. In fact, it was his enemies the Ottomans who first called him Skenderbeg, Lord Alexander, suggesting that his military prowess rivaled that of Alexander the Great. Meanwhile, the pope proclaimed him “Champion of Christ.”

Long after his death, the accolades continued to accumulate. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (who memorialized the expulsion of the Acadians in Evangeline) devoted an epic poem to the Skenderbeg story in 1873. There are statues of Skenderbeg in Brussels, Geneva, and also one in London, which bears the inscription “defender of Western civilization.”

In the Albanian capital Tirana, Skanderbeg Square is much like New Orleans’ Jackson Square – but on a much grander scale. And the fierce, double-headed eagle at the center of the Albanian flag is copied from Skenderbeg’s coat of arms.

It’s not always easy to separate fact from myth, but here is a sketch of the Skenderbeg story as it is commonly told:

When Gjergj Kastrioti was born in 1405, the Ottoman Empire was threatening to engulf all of Europe. Young Gjergj was taken hostage from his home in Albania and brought to the court of the Sultan where he was forced to convert to Islam and trained as a warrior in the empire’s elite fighting force. He distinguished himself as a fierce and capable commander in the Sultan’s service.

At 38 years of age, Kastrioti defected from the Ottoman army, reconverted to Christianity, and devoted the rest of his life to defending his homeland. Successfully uniting various Albanian and Serbian noblemen, he formed an improvised army which he led to defeat the most powerful empire in the world in battle after battle. Many scholars assert that by keeping the Ottomans at bay in the Balkans, he prevented them from overrunning the European continent.

In order to understand what any of this has to do with the people who came to be known as “Arberesh”, we need to follow a small subplot to the Skenderbeg story.

As if Skenderbeg didn’t have enough on his hands fending off the Ottoman threat from the East, he was called upon twice to come to the aid of an ally to the west. In 1448 he sent some of his soldiers to Italy to help Alfonso V, the king of Naples, who was facing a revolt. Thirteen years later Alfonso’s son, Ferdinand I, found himself threatened with another insurrection, and he also turned to Skenderbeg for help, just as his father had done before him.

The cover of a book about Scanderbeg in Bret Clesi’s office, photo by Ellis Anderson

This time Skenderbeg didn’t merely send soldiers. He himself accompanied them across the Adriatic, and upon arriving in Italy, he commanded the combined army of Neapolitans and his own Albanians, defeating the rebels and once again securing the throne for his ally. The Neapolitan kings showed their gratitude by granting land in Italy to Albanian soldiers.

After Skenderbeg’s death, the Ottomans conquered the Balkans, and a flood of Albanians sought refuge in Italy with their kin who had already settled there. Back then, the land that we now know as Albania was more commonly known as “Arberia,” so these Albanian exiles were known “Arberesh.”

While modern historians might challenge some aspects of this story – arguing for example that there were already settlements of ethnic Albanians in what is now Italy before Skenderbeg’s time – to identify as Arberesh today is to see oneself as a son or daughter of Skenderbeg, if not by physical descent, then on some spiritual level. Over the years this story of how their ancestors defeated an army that outnumbered them ten to one has evidently inspired them to resist the equally relentless but far more insidious threat: assimilation.

The fact that they have managed to maintain their identity is truly amazing when you think about it. Not only have they been separated from their homeland by the Adriatic Sea for more than half a millennium. They have also been separated from one another, forced to settle in dozens of isolated enclaves scattered across Sicily and southern Italy. There must have been enormous pressure to be swallowed up by the dominant Latin culture.

The immigration to New Orleans four centuries later opened a whole new chapter in the Arberesh saga. In the melting pot of America (or shall we say the “gumbo pot” of New Orleans?) that pressure to assimilate was evidently much fiercer. The sheer number of New Orleanians of Arberesh ancestry today who have never heard about their own heritage is a testament to this.

There are certainly those who mourn the fact that the flame of Arberesh identity in New Orleans doesn’t burn as brightly as it once did. On the other hand, the very fact that there is anyone left to lament proves that that flame is far from extinguished.

And much of the credit for that belongs to the great grandfathers of Bret Clesi and Charles Marsala along with about a hundred other former residents of a village in Sicily called Contessa Entellina, who came together to form a charitable society in 1886.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of the story in which we focus on the Contessa Entellina Society and the part that it played in securing the survival of New Orleans’ Arberesh community.

One of Bret Clesi’s ancestors, a member of the musical band of the Contessa Entellina Society, 1895.

Your support makes stories like this one possible –please join our Readers’ Circle today!