Marcel Giraud’s Definitive Histories of French Louisiana

La Salle, claiming Louisiana for France, 9 April 1682. Oil on canvas, 1847, by George Catlin

Diligently working for half his life, a meticulous French scholar laid a firm foundation for all future researchers in the multi-volume “The History of French Louisiana.”

— By John S. Sledge

I first encountered Marcel Giraud’s work in the spring of 1987. My friend Johnnie Andrews Jr., a consummate Gulf Coast history connoisseur and master genealogist, was walking me through the French Quarter and detailing its colorful history. I had only recently taken a job with the Mobile Historic Development Commission and was interested in better understanding the central Gulf coast’s Gallic roots.

At some point during our tour, Johnnie led me into a quaint bookshop—alas, I can no longer recall which one—and paused before an entire wall of Louisiana history books. I stared blankly. Perceiving my confusion, Johnnie deftly plucked one forth and placed it in my hands. At roughly 400 pages it was a respectable size but, thankfully, no doorstop. Titled A History of French Louisiana, Volume One, The Reign of Louis XIV, 1698-1715, its modest green dust jacket displayed a colonial-era drawing of Dauphin Island that nearly overwhelmed the author’s name, Marcel Giraud, tucked down at the left corner.

“Buy this one,” Johnnie advised. “It’s all about Mobile and how the French settled the Gulf Coast.” Grateful for his recommendation, I promptly made the purchase.

“History of French Louisiana” in French at Arcadian bookshop in the French Quarter (714 Orleans). Owner Russell Desmond (background) translated volumes three and four, which are still unpublished in English.

Johnnie was right. Giraud’s book detailed how the French-Canadian naval hero Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville probed our region for his sovereign, charting the Mississippi River’s multiple mouths and establishing Biloxi and Mobile, the latter Louisiana’s first capital. It included a fascinating cast of characters—French royals, ministers, financiers, colonists, Catholic priests, Indians, enslaved African people, and the practically ungovernable Canadian coureurs des bois (forest runners) who insisted on living in the woods with their Indian concubines.

There were descriptions of canoes and bateaux, earthen mounds and half-timbered houses, tomahawks and small swords, as well as subsistence agriculture and forest diplomacy. The overarching theme was struggle—of the Crown against scarce resources and European distractions; colonists against the wilderness, the elements, disease, poverty, each other, the English, and the Alabama and Chickasaw Indians; all set against an evocative coastal backdrop of water, mud, marsh, and swaying moss. These 35 years later, the book remains a beloved, well-thumbed mainstay of my library, cited in two of my own books.

When Johnnie and I ducked into that Vieux Carré bookshop, Marcel Giraud (1900-1994) was still hard at work on his history, a magnum opus that would eventually include five volumes. Even at that length, it only covers half of the first French colonial period, 1698-1731. Some historians have joked that had Giraud lived another 100 years, he could have brought the saga all the way to 1769, when Bourbon Spain acquired the colony.

Unfortunately for such a distinguished product of so fine a mind, Giraud’s epic was to suffer a spotty publication and translation history.

Marcel Giraud was born in Nice, France, where his family had lived since the mid 19th century. He took a Bachelor’s degree in 1920 and a Master’s in history the following year from the Université d’Aix en Provence. During the early 1930s he visited British archives and libraries researching a book about Canada. A 1934 Rockefeller Foundation grant allowed him to continue his studies across the Atlantic.

By 1947 he had taken a PhD in history, found an academic berth at the Collège de France in Paris, and published his first book, Le Métis canadien, son rôle dans l’histoire des provinces de l’Ouest (English edition 1986 The Métis in the Canadian West). This book carefully examined the complex history of the French and Indian blended communities on the Canadian prairies. Unfortunately, contentious modern politics between French- and English-speakers there engulfed Giraud, prompting him to seek a less controversial topic.

He found it in French Louisiana’s eventful history, a subject practically untouched except by romancers and narrowly focused specialists. Thanks to a second Rockefeller Foundation grant after WW II, the then middle-aged Giraud traveled to the Pelican State where he spent a long summer scouring colonial documents.

“I thought that having grown up in Nice I was prepared for the heat of New Orleans,” he recalled in a 1993 interview with Vaughn B. Baker published in the journal Louisiana History. “But I had never imagined such heat as Louisiana.”

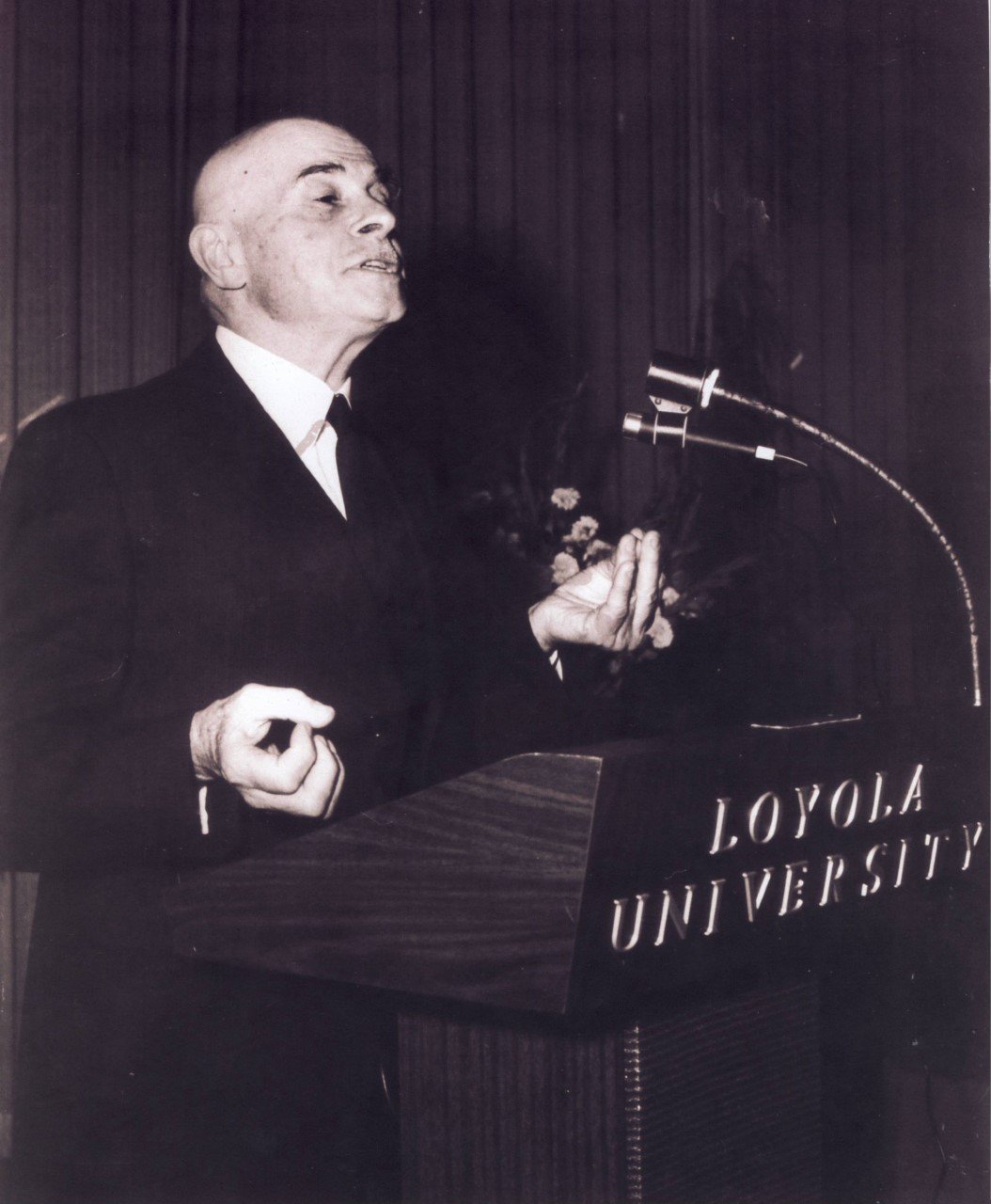

Photo of Marcel Giraud taken at Loyola 1967 by Gilles-Antoine Langlois

When one considers that Giraud labored before the blessings of widespread air conditioning, his achievement becomes all the more impressive. Daunted but undeterred, he won the trust of the Louisiana Museum’s curator, obtained a key, and pursued his investigations deep into the night. He was likely the first person to touch the records in over 175 years.

“The documents were given to me in boxes, unsorted, eaten by termites, many of them unreadable,” he told Baker.

Giraud’s goal was to write a political and administrative history of the French colony by probing meeting minutes, court records, official correspondence, baptismal records, reports, and maps. Upon his return to France, he deepened his research at the Archives of the Colonies, the Archives of the Navy, the Manuscripts of the Bibliothèque Nationale, and the Archives of the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice. He was thorough and hoped his resulting books would fully explain exactly how the colony did, or did not, function.

Of interest were “how the French took possession of the land; what the phases and nature of the exploitation were; what kind of society emerged in Louisiana; what life was like in the settlements; ... and what problems grew out of the colonists’ contact with the natives.” (vol. 1, p. xi).

Presses Universitaires de France published the first volume of Histoire de la Louisiane française in 1953. Scholars were impressed and urged an English translation. Competent scholarly translation requires significant resources and time.

Happily, LSU Press committed to the project, and in 1974 offered an English edition by native Mississippian Joseph C. Lambert. The American reviews were effusive. Writing in the William and Mary Quarterly in the spring of 1975, John G. Clark declared the work “essential, thoroughly researched, and reliable.” That December, a writer for the American Historical Review pronounced it “scholarly and definitive.” A year later, Louisiana History praised Giraud’s “inexhaustible erudition and consummate art.”

All the while, Giraud steadily produced more volumes. The second, Annés de transition, 1715-1717 came in 1958; the third, Histoire de la Louisiane Française, L'époque de John Law, 1717–1720 in 1966; and eight years later the fourth, Histoire de la Louisiane française, La Louisiane après le Système de Law, 1723.

Cover of Volume Two, click to order from LSU Press

These volumes dealt with New Orleans’ 1718 founding and early years, Jesuit and Capuchin religious scuffles, and the Scotsman John Law’s ill-starred Company of the West. Giraud subsequently submitted a fifth manuscript, but his publishers refused it. Presses Université blamed poor sales of the previous books and doubted that investment in a fifth was justified. Editions L'Harmattan corrected this indignity in 2012, when it published the manuscript as Histoire de la Louisiane française: La Compagnie des Indes (1723-1731) thus completing the set in Giraud’s native tongue.

The path toward the set’s English-language publication started well but eventually fizzled. Long after its release of volume 1, LSU Press commissioned the prolific British scholar Brian Pearce to translate volumes 2 and 5. Pearce was a legendary figure, a famed Marxist as well as an enormously productive translator. He tackled volume 5 first, which LSU offered in 1991 as The Company of the Indies, 1723-1731. Volume 2, Years of Transition, 1717-1719, followed two years later.

Hoping to complete what LSU, Lambert, and Pearce had thus far achieved, The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC) commissioned Russell Desmond of Arcadian Books and Prints to translate volumes 3 and 4.

In a recent telephone interview, Desmond recalled the project and its difficulties. These included numerous arcane military and naval terms as well as Giraud’s sometimes “ambiguous phrases.” Despite these challenges, Russell dubbed Giraud “a genius.” The French historian’s habit was to work closely with his translators, but his death derailed the project.

Desmond fulfilled his obligation, but neither THNOC nor LSU opted to publish the resulting manuscripts. Serious researchers may access them in THNOC stacks. Therefore, the only English translations readily available to date are volumes 1, 2, and 5 – a frustrating circumstance not only for scholars but also general readers looking to dig a little deeper into an intriguing subject.

None of this should diminish Giraud’s overall achievement. The historian Carl A. Brasseaux, a former director of the Center for Louisiana Studies at Lafayette and author of over 30 books, opined that A History of French Louisiana “constitutes the cornerstone” of this region’s colonial studies.

Greg Waselkov, a retired University of South Alabama archaeologist who spent years excavating the original Mobile town site, agrees. In a recent email, Waselkov wrote that Giraud’s work has “lasting value. I’m sure he wasn’t infallible, but I’ve not found serious errors in his narrative, and I always start with him when tackling a new research project.”

A History of French Louisiana is not a beach read. But anyone interested in a fuller appreciation of the Gulf Coast’s French heritage will find it profoundly illuminating.

Earliest published depiction of New Orleans, 1720, appeared as an ornament in a French map. Clearly it is not a depiction of the young city on the Mississippi River; it may actually show the early French settlement at the mouth of Bayou St. John.

Support our creative team –become a member of our Readers’ Circle now!