It's Fruitcake Weather

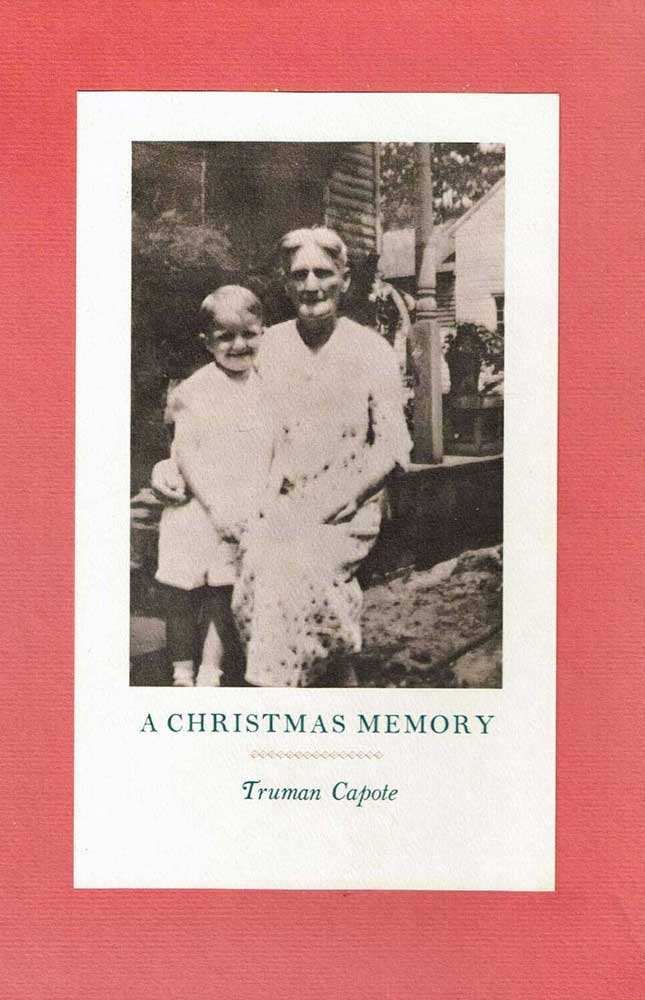

Truman Capote and Sook

Truman Capote's A Christmas Memory possesses the power to make even contemporary readers summon up their own most-cherished holiday recollections.

-by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

I try to remember to reread Truman Capote’s A Christmas Memory every year during the holidays, and this year my book club reminded me.

“It’s fruitcake weather,” Sook says to Buddy, and they are off to the races – and the pecan grove, the grocer’s, Haha the moonshiner’s, the post office.

It is the perfect story, told in the simplest and most heart-rending way. It is Truman Capote at his best, which is stellar.

One year in the late 1970s, ’77 I believe, I was privileged to sit in an old gymnasium building on the Auburn University campus and hear Capote read his own words. The gym by then was called the Student Activity Building, and events that didn’t attract the coliseum-sized audiences of Three Dog Night and Ike and Tina Turner were held in it. Journalists and poets and others who didn’t draw crowds “played” the Student Act.

A couple of decades later the building would be ignited by a careless tailgater’s grill during a football game and burn to the ground. People made jokes about the Student Act being put out of its misery, but I was sad. All I could think about was the fact Truman Capote had read aloud there.

I already was familiar with the story – I’d lived a year and change in Monroeville, Ala., the setting – and loved the perfect words, each one chosen like a ripe peach at market. But, believe it or not, I’d never heard Capote speak, never heard his voice, though I know he must have been on television hundreds of times by then.

When Capote began reading in that childlike, inimitable voice, I cringed. Oh, no! That’s not how that beautiful story’s supposed to sound. It was Minnie Mouse during puberty.

Truman Capote in 1959, about ten years after he worked on his first novel, "Other Voices, Other Rooms," in the French Quarter, at 711 Royal Street. Library of Congress photo by Carl Van Vechten.

But like a singer singing his own song, pretty soon it became clear that, of course, it was exactly how the words were supposed to sound. And Capote’s almost shocking lispy soprano was perfect to be the voice of Sook saying, “I made you another kite.”

My love for this Christmas story grows as I get older. It has everything, including a dog that dies; the dog always dies in the end. Now I am more than aware of how hard it is to write in such true rhythm with economy of narrative.

I suppose it doesn’t hurt that I spent a year in Monroe County, in the same rural setting Capote described. I cut a Christmas tree in the same native woods, getting lost in the process.

“Always, the path unwinds through lemony sun pools and pitch vine tunnels….”

The ruins of Capote's childhood home in Monroeville, Alabama. Library of Congress, photographer Carol M. Highsmith.

Perhaps the best Christmas of my life, or one of the best, was spent in a big house in a bosky oasis inside the Monroeville city limits but as secluded as Mongolia. My first husband and I decorated with fresh greenery and real candles and invited everyone we knew in town to come sing carols. It’s a wonder we didn’t burn down the landmark house, built by a local lawyer and, after his death, inherited by his daughter, who had no apparent desire to stay in Monroeville.

We didn’t have a cent but were caretakers for the hacienda-style mansion with its fabulous but dry-rotting furnishings. At the old upright piano we sang in our best carol voices, fueled by love and youth and beer and enthusiasm for life. As Bob Seger sang, “wish I didn’t know now what I didn’t know then.”

In truth, the house made me a tad miserable because I knew I’d never own it; even my romantic nature had to come to grips with that. For one thing, the daughter didn’t want to sell it, and, if she had, the asking price for the tile-roofed mansion would have been more than a couple of reporters for a weekly newspaper would see in their lifetimes.

Hybart House in Monroeville, where Rheta spent one of her favorite Christmas days.

But for a short, magical, miserable while we were actors in a play with a grand set, seeing our reflections in borrowed mirrors and hearing the clock strike vanishing hours. That Christmas gathering was one of our best ever, both because of the house and despite it. I’ve never lived anywhere as grand since.

It was a cold Alabama winter that followed the giddy December, and the house was too much to heat with its high ceilings and endless rooms. We kept the kitchen and one bedroom warm.

One week the water in the toilet bowls froze, and we decided perhaps some practicalities were more important than sun porches, gilded mirrors large as pool tables and 10-foot-tall mahogany secretaries.

We moved back to Auburn.

What Capote tapped into, of course, is that all of us have a Christmas memory, though few of us can spin it into gold for others. Life has been so good to me, and I am surrounded by friends and enough family and dogs that forgive and forget. I think to have seen the woods that Truman Capote describes and to have smelled and touched its bounty is as close as you can get to writer’s heaven.

Help support our creative team –become a member of our Readers’ Circle now!