Dixie's, Yuga and Gay Carnival

1/26/2020The first gay Mardi Gras pioneers powered through many challenges - including a police raid on the fifth annual Krewe of Yuga ball, where nearly 100 men were arrested.

- by Frank Perez

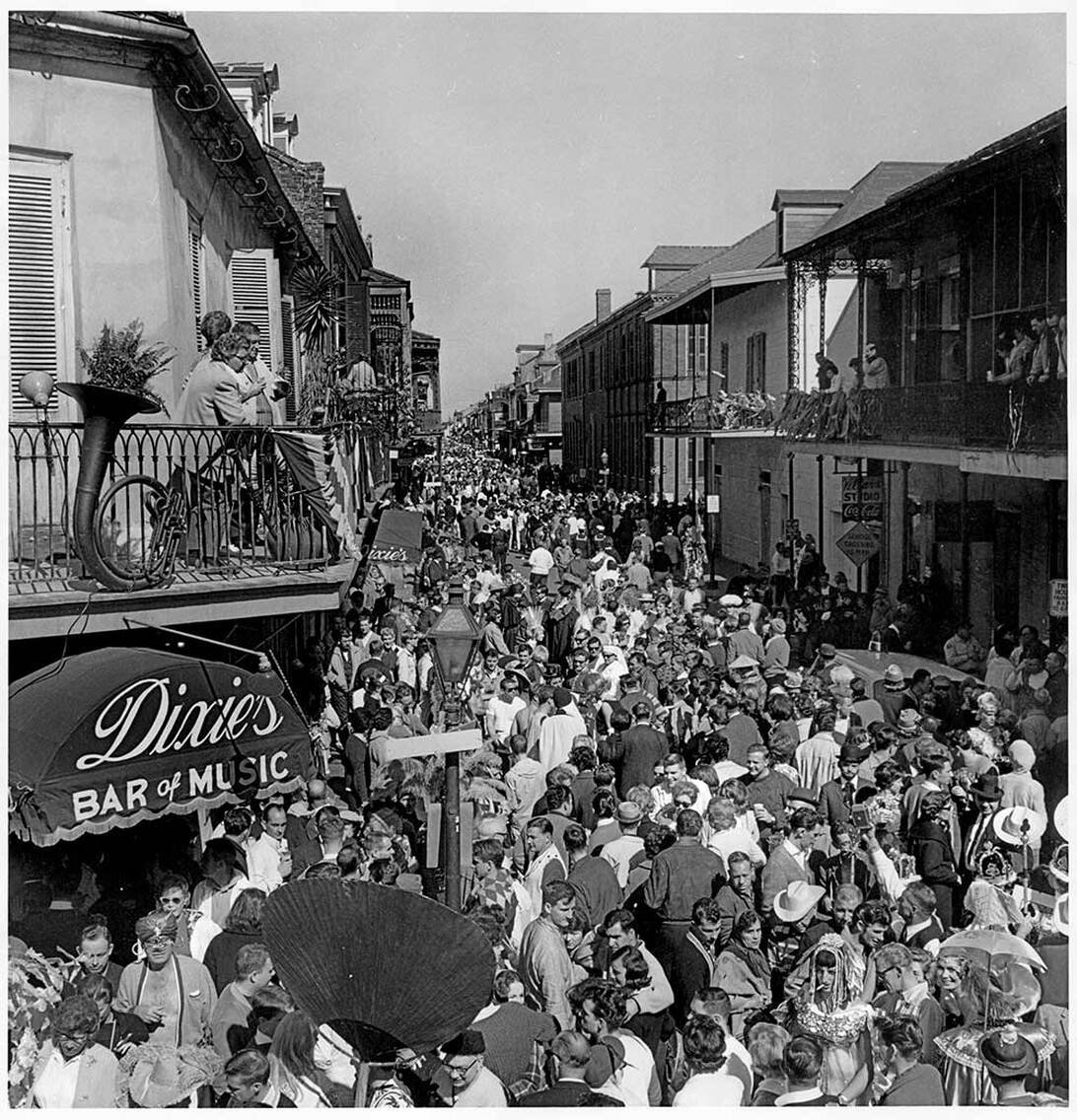

In the 1950s, the epicenter of gay Mardi Gras in New Orleans was the intersection of Bourbon and St. Peter streets. There, on the downriver side, were Dixie’s Bar of Music and across the street, the Bourbon House. Above the side entrance to Dixie’s on St. Peter was a sign that read “For Male Bachelors Only.” Several of the bachelors in that line would eventually form the first gay Carnival krewe - the Krewe of Yuga.

Mardi Gras, that sacred day of days marked by wanton abandonment and Baroque fantasy, has long been revered by gay men. Much like the Quarter itself, Carnival is a wonderfully complex cultural phenomenon, replete with layers of meaning and symbolism. It is revelry, pageantry and fantasy; who better to embody it than gay men?

Drag, of course, has always been a part of Mardi Gras. In fact, a man in drag is the subject of the first written reference to Mardi Gras in New Orleans. In 1729 Marc Antoine Caillot, a bureaucrat working for the Company of the Indies (whose offices were along Decatur between St. Peter and Toulouse streets), wrote in his journal:

“The next day, which was Lundi Gras, I went to the office where I found my companions bored to death. I proposed to them that we mask and go to Bayou St. John . . . As for myself, I was dressed as a shepherdess, all in white. I had a corset of white bazin, a muslin skirt, a large pannier . . . I had some beauty marks too. I had my husband, who was the Marquis of Carnival . . . What made it hard for people to recognize me was that along with having shaved very closely that evening I had a number of beauty marks on my face and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up . . . unless you looked at me very closely, you could not tell that I was a boy.” (A Company Man, Erin M. Greenwald, Ed., THNOC)

In the 20th Century, one of Mardi Gras’ great appeals to gay men was that it was the one day out of the year when cross-dressing and masking were permitted. This is evident in the Bourbon Street Awards—a costume contest held annually on Mardi Gras afternoon that, for the most part, features elaborate costumes made for the tableaus at the gay Carnival Balls earlier in the season. The Bourbon Street Awards was founded in the 1960s by Arthur Jacobs, owner of the Clover Grill, as a way to drum up business for his diner.

Bourbon Street during Mardi Gras, in front on DIxie's. The Richard R. Dixon/Cole Coleman Collection, gift of Mr. & Mrs. Richard R. Dixon, The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1980.257.69

A detail from the remarkable photograph above. The Richard R. Dixon/Cole Coleman Collection, gift of Mr. & Mrs. Richard R. Dixon, The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1980.257.69

While Mardi Gras is still immensely popular among gay men, it’s safe to say that Southern Decadence has surpassed Fat Tuesday as the premier gay holiday in the city. For the gay krewes, none of which parade, the Carnival balls are the pinnacle of the season.

The first gay krewe - Yuga - grew out of a house party. Doug Jones lived on Carrollton Avenue and each year would host a parade viewing party for the Krewe of Carrollton parade. Among his friends were Elmo Avet, John Bogie, Claude Davis Jr., John Dodt, Stewart Gahn, Tracy Hendrix, James Schexnayder, Clay Shaw, and others.

In 1958, these men, many of whom were members of the mysterious (and enduring) Steamboat Club, which had been founded in 1953, formalized their annual party by calling it a ball and proclaiming themselves the Krewe of Yuga. Yuga was a group of older, well-established men who escaped their straight, Uptown lives by congregating in the Quarter at Miss Dixie’s.

Dixie, herself a lesbian, affectionately called them “the cuff-link set.” From the hub of Dixie’s, they would frequent other “queershops,” as the police derisively called them, such as Tony Bacino’s, Café Lafitte in Exile, and the Starlet Lounge.

Jones was a Carnival enthusiast and appreciated its history. His family had ties with Proteus, and it was the 1889 Proteus parade theme—"Hindoo Heavens”—that inspired the name Yuga. In Hindu mythology, the Kali Yuga was an epoch of time.

Yuga’s first two balls were held at Jones’ home. Just about everyone was in drag and the parties, which featured “debutramps” instead of debutantes, were enormously popular. Otto Stierle is quoted in “Unveiling the Muse” as remembering, “everyone arriving at the house had to be in costume and climb a large staircase in front of the house to reach the second-floor entrance, a spectacle for an otherwise quiet neighborhood.” (Smith, Howard P. Unveiling the Muse: The Lost History of Gay Carnival in New Orleans. UP of Mississippi, 2017)

By the third year, it was clear the Ball would have to be held elsewhere. In 1960, Yuga left Uptown for the lakefront and held their ball at Mama Lou’s jazz club on Lake Pontchartrain. The following year the ball moved to Metairie to a venue called The Rambler Room, which was a dance studio attached to a day care facility at which one of the krewe’s members worked. The location was perfect, and Yuga scheduled their fifth ball there. But the fifth Yuga ball was ill-fated.

An ill-fated invitation: the 1962 ball was ended by a police raid, resulting in a 100 arrests. Image courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Tracy Hendrix, acc. no. 1980.178.71

The 1962 ball was off to a good start. The costumes were fabulous, alcohol was flowing, and aging French Quarter legend Elmo Avet, who owned an antique store on Royal Street, dressed as Mary Queen of Scots awaited being crowned Yuga Regina V.

But it was not to be. Before the tableau began, Jefferson Parish police arrived at the Rambler Room, kicked open the doors, and raided the ball. Pandemonium ensued and many fled the building by jumping out of windows. Several ran into the adjacent woods but were stopped when the police dogs approached. Nearly 100 men were arrested.

Those who escaped arrest eventually made it back to the safety of the French Quarter. Miss Dixie, upon being alerted of the raid, dispatched her attorney with a wad of cash from her bar safe to bail everyone out of jail. The morning following the raid, Elmo Avet and Bill Woolley, both of whom avoided arrest, sat at the Bourbon House across from Dixie’s and debriefed the previous evening’s fiasco.

Image by Norman Thomas, 1958 or 1959, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1988.107.37

So who tipped off the police? It’s easy to assume the conservative, suburbanite housewives of Metairie in 1962 naturally called the police when they saw a bunch of men dressed in drag entering their local day care facility, but a much more tantalizing theory involves a jilted drag queen. Hell hath no fury . . .

Candy Lee hailed from Cajun country and found her way to New Orleans where she secured work as a “female impersonator” at the legendary Club My-O-My. She also worked as a bartender at Tony Bacino’s, which in 1958 was raided several times by the police. Candy Lee was arrested multiple times.

Convinced the raids were the result of a tip to the police from a fellow queen who had a proverbial axe to grind with her, Candy Lee, never one to be soft-spoken, loudly and repeatedly told several people whom she thought had snitched on Tony Bacino’s. Her accusation was never verified, and it may not have been true at all since the Mayor’s “Committee on the Problem of Sex Deviates” - created to rid the French Quarter of homosexuals - harassed several “queershops.”

Candy Lee raised so much hell about the raids that by the early 1960s, she had been banned from the two gay krewes at the time—Yuga and Petronius—and was generally considered a persona non grata.

In the aftermath of the 1962 Yuga raid, many speculated, among them Yuga founder Doug Jones, that Candy Lee had tipped off the police that a wild stag party involving cross-dressing homosexuals was occurring at the Rambler Room, thus exacting her revenge.

Mardi Gras, possibly at Dixie's Bar. Image by Joe Wilkins, 1965The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Joe Wilkins, acc. no. 2011.0378.48

Candy Lee became something of a legend when she inspired Tennessee William’s And Tell Sad Stories of the Death of Queens. Lee and Williams had become friends and the playwright was fascinated by her life-story. Lee often regaled Williams with the various tales of woe that constituted her life at bars in the Quarter and at her apartment on Decatur Street.

Lee and Williams and Jones and Dixie and Yuga are long gone now but gay Carnival survives and continues to add layers of complexity to a tradition begun on Shrove Tuesday 1699, when Iberville and his younger brother Bienville, who lived into his 80s and never married, docked their pirogues and made camp near present day New Orleans. They dubbed a nearby bayou “Bayou Mardi Gras” and called the settlement “Pointe du Mardi Gras.” (Take that, Mobile!)

Works Referenced:

Caillot, Marc A. A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies. Erin M. Greenwald, ed., Lori Boyer, trans.

Smith, Howard P. Unveiling the Muse: The Lost History of Gay Carnival in New Orleans, University Press of Mississippi, 2017

This comprehensive exhibition is open until December 6, 2020.

Full photo of Dixie's at Mardi Gras (detail at top). Photo by Stephen Scalia circa early 1950s, courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Stephen Scalia, acc. no. 2012.0172.26.

Images in this piece provided courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection, which is currently offering a special Mardi Gras tour until February 21, 2020. See full tour details here.