Strong as the Currents

September 2019Meet the hardy folk who ply the waters of the country's "last frontier" in Melody Golding's new book Life Between the Levees.

- by Scott Naugle

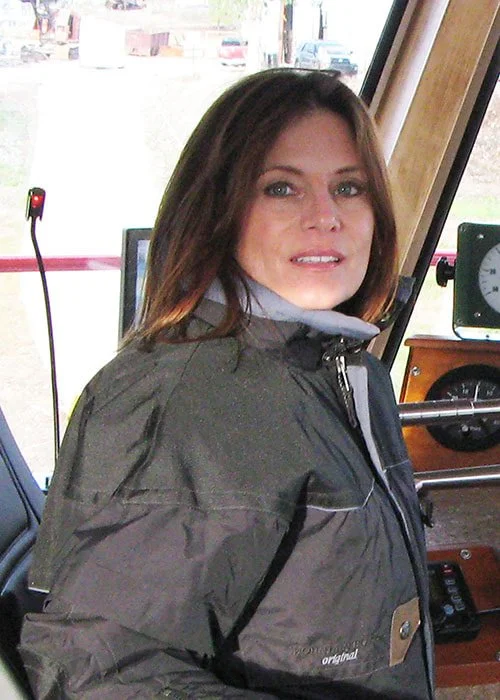

photos by Melody Golding

It is both lagniappe and ironic that the word “levee” is believed to have been first used in 1718 in New Orleans. It is derived from the French word “lev´ee” which means to raise. Four hundred years later, our levees in and around New Orleans remain not only as an engineering feat, but as an enduring influence on our culture and lifestyle.

In Life Between the Levees: America’s Riverboat Pilots, Melody Golding assembled dozens of interviews with riverboat pilots working across many of our navigable waterways from the Mississippi River to the Allegheny River in Pennsylvania. The experiences of the pilots span more than 100 years, beginning on 18th century steamboats to GPS-fitted vessels in the 21st century.

Golding comes “from a river family.” Her husband, Steve, has been in the riverboat and barge business in Natchez, Miss., for 45 years. “Our second date was a trip down the Mississippi River in May of 1979 from Vicksburg to Natchez on the old M/V (motor vessel) Martha May.”

“It took me 10 years to capture all of these stories,” explained Golding as we chatted. “There are 12,000 navigable miles of waterways in the United States spanning 38 states. I traveled from St. Louis to Houston, up the Ohio River, and down to New Orleans to speak to all of these pilots. My husband calls our waterways the last frontier.”

Riverboat pilots hold the unique perspective of living on both sides of the levee. While they have families, mortgages, friends and homes to maintain on the dry side of a levee, pilots also ride and navigate the swift, deep, dark and mysterious currents of a river as they steer their boats and cargo to port.

A professional pilot is defined as professionally as someone who is skilled at navigating waterways. Some have areas they specialize in, like the Mississippi River "bar pilots," a select group who board large ships to help them navigate the treacherous currents and bends from the mouth of the river to Baton Rouge. Others have more generalized training.

While all captains have been trained as pilots first, explains Golding, not all pilots become captains. Captains also are charged with the oversight and responsibility for the vessel and the crew.

The trips on the water often last for days or weeks. Strong bonds with one another are forged. “This is a unique occupation where you live where you work,” said Golding.

Harold Schultz became a riverboat pilot when he was 15 years old in 1955. “I grew up on a bayou in Louisiana - little place called Lafitte. My grandfather, when he was alive, and my grandmother, they had a houseboat right there on the bayou. That’s where I grew up… They were shrimpers and trappers,” recalled Schultz.

Schultz’s first boat at 13 was a pirogue. He was trained two years later in a commercial craft by his “mama’s cousin.” Schultz never forgot his advice: “I’m going to train you to run anywhere, you know. I’m going to teach you how to navigate. A lot of people can steer a boat, but not many can navigate. If you can navigate, you can go anywhere that you’ve never been before.”

Golding, in her third book, continues to find subjects who offer a distinctive and often overlooked perspective. As a photographer and researcher, she reveals and highlights voices and cultures that may not have been privileged with a mainstream spotlight.

In Katrina: Mississippi Women Remember, Golding’s black and white photographs underscore the personal, first-hand narratives written by more than 50 women.

Golding’s second book, Panther Tract: Wild Boar Hunting in the Mississippi Delta, focuses on the danger, thrill and tradition of boar hunting in remote areas of Mississippi.

Color photographs by Golding are generously interspersed throughout Life Between the Levees. Lines of tow barges, ropes as thick as a weightlifter’s arm, images of the sun-lined and river-wise faces of several of the captains and the locks of the navigable waterways in Pennsylvania are all captured in both vivid and nuanced interpretations.

“All my family, my uncles, my dad, and everybody worked on dredges or were towboaters. I came from a mariner family,” explained Jody LaGrange. “This life is rough. You’re away from your family a lot and miss a lot of stuff, but it is a good living, and it’s a good career.” LaGrange was born in 1970.

While Life Between the Levees includes interviews from riverboat captains working on navigable waterways across the United States, LaGrange stated, “I think that people in south Louisiana are better mariners because they grow up on the water. A lot of them were shrimpers when they were younger.”

There is an aspect of piloting a boat on the lower Mississippi that is unique to Louisiana. “Sometimes on the boat I’ll speak French,” noted LaGrange. Several other interviewees also commented on the use of French while on the waterway. “It takes me a while to think about what I need to say in French. But if they are talking on the radio, I can understand what they are telling me.”

It is not all back-breaking, relentless work on the river. There are moments of levity. LaGrange recalled a special night on the Mississippi.

“We were coming down on Peoria bridge, and it was at night. ‘Hey captain, you really need to put your spotlights on that boat over there and see this.’ We put the spotlights on, and they had about four strippers on a pole that were dancing on there. They had a banner that said ‘Come and meet your local strip club.’”

Woman have integrated the wheelhouse. Born in 1958, Terri Smiley began on the river as a towboat cook. In 1984, she was first told she was too young to go out on a boat. Cooks “had to be old, fat, ugly, one foot on the banana peel and the other one in a bucket.”

She worked her way up to become a deckhand and then in 2005 made it to the wheelhouse as a riverboat pilot.

The personalities and their memories as memorialized by Golding are as diverse, spirited, and strong as the currents within the Mississippi River. Eleven of the interviewed subjects have passed away.

“I’m very proud to have preserved their stories,” said Golding, “along with all of the others. Every one of them is unique and special.”

Your donations make stories like this one possible: