Going to Pots in New Orleans

Floyd (far left) and partner Frank Gagnard (far right), longtime art and theatre critic for the Times-Picayune, holding court at Pat O'Brien's. Photo courtesy Floyd McLamb

Floyd McLamb: a sharecropper's child from North Carolina turned high-powered French Quarter businessman reflects on the "high cotton" days in the neighborhood.

-by Andrew Cominelli

Floyd Lamb’s first job was assigned to him when he was about nine years old.

His parents farmed cotton and tobacco in Erwin, the tiny North Carolina Baptist town where Floyd grudgingly grew up. They had 17 acres, and grew tobacco on 3 of these. His father also sharecropped on a neighbor’s land, splitting his crop’s payout with the neighbor as rent.

For the McLambs, farming was a family affair. Typical for the time and place, local schools excused farm kids from the first month of classes so they could work the harvest. Floyd’s father brought him and his siblings still living at home into the field, a motley team of farmhands ranging widely in age and height. Each had a role in the factory-like system of field work. One’s job depended on age, size and strength.

Nine-year-old Floyd’s first job was to schlep a bucket of water around the field for workers to drink. The premise of this job was oddly corporate and draconian; the job existed, in part, to make sure others didn’t have to stop working.

His second job came during cotton season. Despite the family’s need for able bodies, his mother refused to work with tobacco on obscure religious grounds. But she picked cotton - a plant above-board with her God - faster than anyone else. Young Floyd pitched in by hauling his baby brother, Kenneth, out to his mother so she could nurse him right where she picked.

Now 84, McLamb believes that the slight list in his walk comes from carrying Kenneth on his hip, across cotton fields, in the mid-1940s.

Floyd McLamb at his Popularville farm

Since then, McLamb has had an almost inhuman capacity for hard work.

His first job in New Orleans was at a welding company’s office on Tchoupitoulas. He sat fielding phone orders, writing letters and balancing the books. He inflicted constipation on himself by refusing to get up and go to the bathroom. It earned him a raise -- from $250 to $350 per month - but was fired weeks later when the company decided they couldn’t afford him.

New Orleans was a far cry from Erwin, but Floyd brought his family’s grim work ethic to the French Quarter. Ironically, he drew much of his doggedness from his desperate refusal to go back to the country.

Unsuited to interviews and other formalities of the urban working world, McLamb drifted through periods of unemployment. He taught English at McDonough for a year before he finally got an opportunity he could work with.

With school out for the summer, Floyd picked up a job managing the Old Coffee Pot. He’d had a stressful year as an English teacher. On his first day one student chased another with a hatchet. He’d made a ritual of coming to the cafe after work to tank up on coffee, see friends and unwind. He became such a familiar and trusted face that the owner, Miss April, asked him to manage the cafe in her stead while she left for the summer.

Floyd at the Coffee Pot, courtesy Floyd McLamb.

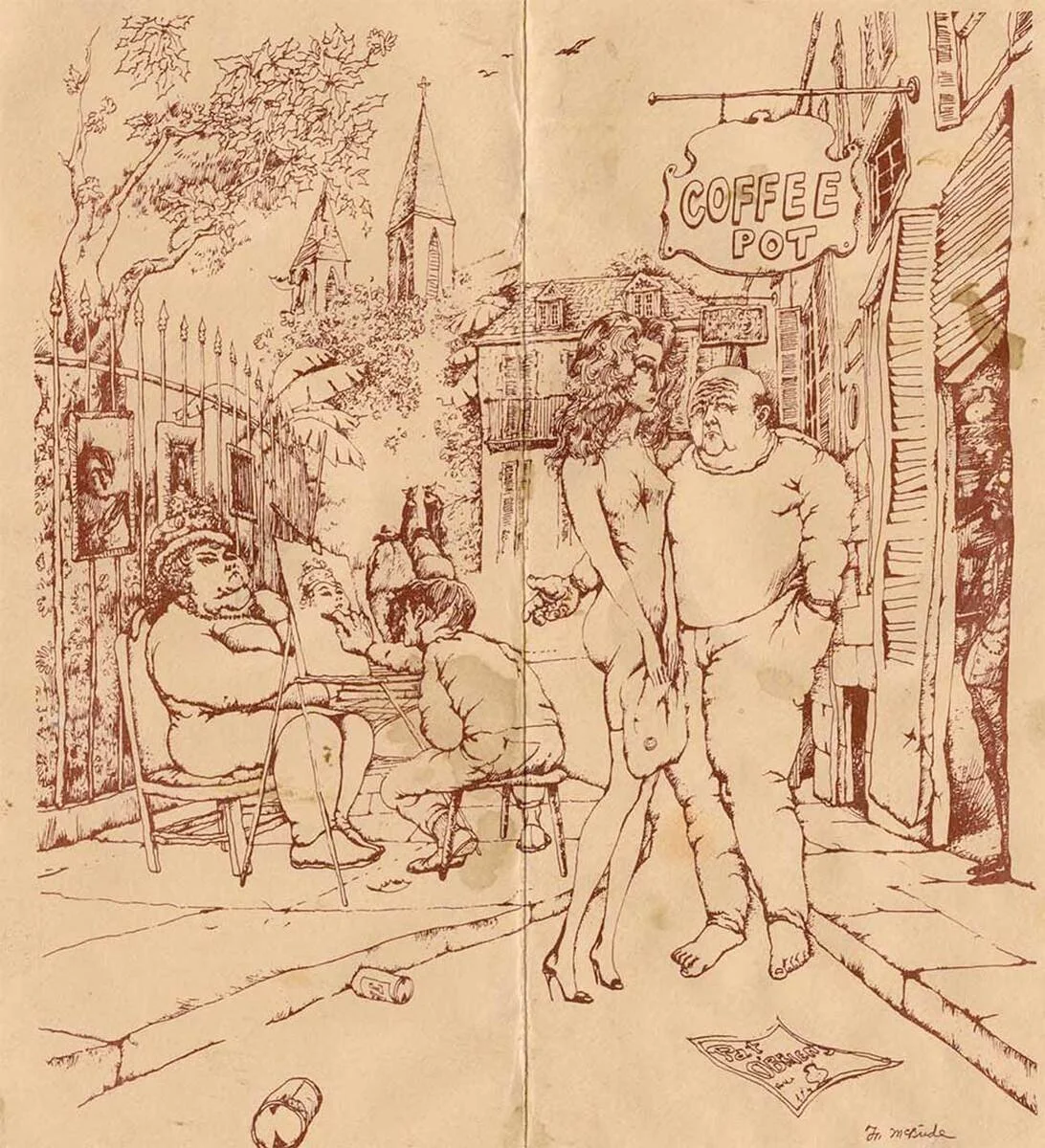

A menu cover, courtesy Tulane Special Collections

The cafe was on life-support, and Floyd nursed it back to health. He ran a tight ship and started turning a profit. Despite little business experience, Floyd perceived the value of customer service.

“What has a small business got but their charm and personality?” he says. “It takes more than just work. It takes a concern for the customer.”

Miss April returned at summer’s end to a Coffee Pot buzzing with customers. McLamb remembers her walking in on a group of 19 tourists awaiting their food. A flustered Floyd told her he was out of salad ingredients, so she ran down the block to the A&P store. She returned with a single head of lettuce and two tomatoes. Floyd threw up his hands and walked out.

Months later, Miss April asked Floyd if he’d like to buy the Coffee Pot. The asking price was $6,000. She wanted a third of that in cash, up front, and would let him pay the balance back without interest. Floyd called his sister, and she agreed to lend him the initial two grand.

“This was the most exciting day of my life,” Floyd says. “It was like I was floating. I knew instinctively that this was my chance. It opened up a world to me.”

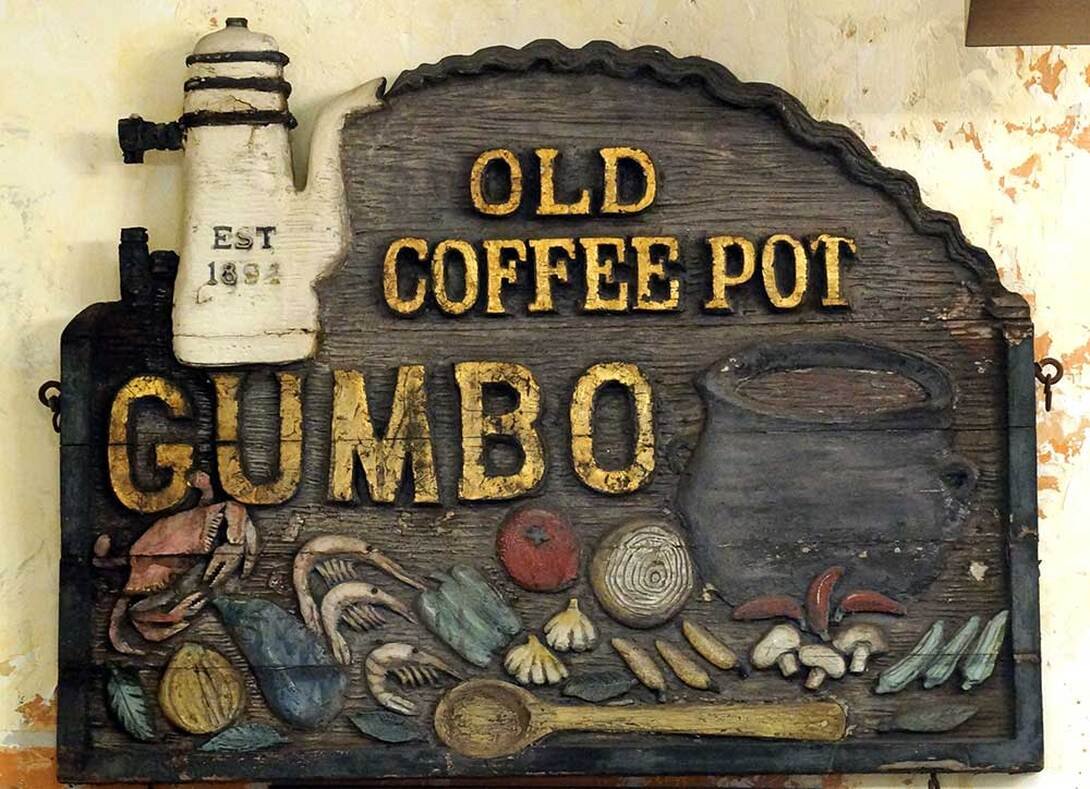

Currently, the Coffee Pot location is occupied by Café Beignet, but the old signs are used as part of the décor.

Once it was his, Floyd dialed up the amount of work he put into the Coffee Pot. He repainted the whole place by himself, sleeping on a pile of tablecloths between painting shifts. He worked there from 6:30 a.m. to 11 p.m., almost every day.

Floyd made the Coffee Pot - which opened in 1894 - his own. As he tells it, he was always there, injecting the place with his personality. When a group of German tourists got impatient, Floyd told their waitress, “I’m getting damned tired of this.” The waitress returned to the Germans. “My boss said he was damned tired of this,” she reported.

Floyd developed a regular clientele that gelled into a kind of salon -- artists and workers converged at one table, drinking coffee and chatting all day long. Breakfast was 25 cents, coffee was 10 cents. He managed a staff of characters, lovable misfits he constantly had to get back on track.

He found clever ways innovate and diversify. The Coffee Pot had a porte cochere that he transformed into a gallery of local artists’ work. One thing led to another, and Floyd soon opened an art gallery, The Paint Pot, right across the street. He posted a sign in The Paint Pot: “If you can’t live without it, come find me across the street.”

With tireless work and a slapdash, but intimate, way of doing business, Floyd made the Paint Pot gallery successful. “I was very good with people who wanted to buy something but said they couldn’t afford it,” he says.

He refused to believe these people. Can’t afford it? Well, how much had they paid for their shoes? How much did that dress cost? Floyd noticed their expensive jewelry and watches and leveraged these details, point blank, against them. Soon they’d leave the gallery with their purchases in tow.

Gallery ownership taught Floyd that framing paintings was profitable in its own right. He saw another opportunity. Soon he opened the Glue Pot, a framing studio.

His career was becoming a sustained chain reaction, his little epiphanies bringing him from one successful enterprise to the next. At one point or another, Floyd owned a plethora of places that today’s New Orleanians know well, like the Golden Lantern and Elizabeth’s restaurant.

Floyd’s success is as distant as it is inspiring. The mechanisms of action that allowed him to climb the ladder don’t exist anymore. Nobody in the 2019 French Quarter gets hired at a restaurant, as a temporary manager, and turns the place around. Why not?

And the $6,000 Floyd paid for the Coffee Pot, adjusted for inflation, is just short of $55,000 in 2019. Getting a restaurant for that price, today, on one of the Quarter’s busiest blocks, could only happen by the kind of major fuckup that leads to heads rolling across low-pile corporate-office carpeting.

Floyd is the only person I’ve ever met with a bonafide Horatio Alger story. What am I to make of it? He reminisces on his “good old days,” free-associating from one foible to the next.

In my imagination Floyd’s mid-century Quarter radiates a specific orange glow. It is always daytime there; the sunshine is always gentle, fixed at the perfect warmth. The people are entertaining or brilliant or both. Artists wear berets. Servers and laborers dispense quips that you can spend your life fondly remembering. Police officers are fat, hapless and harmless. Personal vendettas are setups for hokey punchlines. The comically indignant chase their enemies out the door and down the street, never to be heard from again. All confrontation devolves into farce. Nobody ever gets hurt.

The "Family Table" at the Coffee Pot, reserved for regular locals, many of them artists. Photo courtesy Floyd McLamb.

Floyd casts a kind of spell as he talks. From my many hours in conversation with him, I’ve developed a nostalgia for something I’ve never experienced, for something that maybe never existed. A weird nostalgia for a French Quarter which seems a few ticks closer to some ideal Quarter.

It becomes tempting to think that I found the Quarter way too late, long past its prime, that its essence has drifted away forever, and that all we have left, now, are cheap facsimiles and faulty memories. It’s strange: we are predisposed, somehow, to see an old snapshot of a place as the one true version of that place, and to see our own, present experience of that place as a forgery.

Floyd’s “good old” Quarter is a Quarter without me or anyone I know. But I’m still mesmerized by it, enamored of it. It seems to fulfill a certain promise. I want to sit at that table, with the other regulars, drinking coffee and talking for hours, day after day, that orange glow splayed on the floor tiles and the whole world calm, free and endless.

But this is false nostalgia talking.

I met Floyd about four years ago, at his home on the outskirts of Poplarville, Miss.

My friend Harriet drove us up from New Orleans to see about helping Floyd write his autobiography. Harriet pulled off the road and down a drive carpeted with pine needles and walled by tall azaleas. She parked and we got out and stood around under the pines. The land was pretty, everything reddish-brown and green and softly swaying. Floyd’s house stood before us, brown and unassuming. Birds chirped, a breeze shook leaves from the branches overhead. Where was Floyd?

We went into the house and Harriet called his name a few times. We walked through to the back porch. We stood around some more.

Engine noise cut through the afternoon, strengthening toward us. Soon a four-wheeler materialized in the middle distance. On it was Floyd, an 80-year-old man with a baggy sweatshirt hanging off him, both hands gripping the four-wheeler’s handlebars. He parked and dismounted.

He greeted us perfunctorily; his demeanor was of one interrupted from significant work. He had been across the street clearing land, prepping it for the Japanese garden he planned to build.

In retrospect, I couldn’t have met Floyd at a more characteristic moment. He was 80 years old and lacquered in sweat, worn down from hours of menial labor on the property he’d already worked his whole life to buy.

Floyd had made this his permanent home a few years earlier. He’s called this property “High Cotton,” in reference to an old Southern expression. If someone’s doing well for themselves financially, Floyd would later explain, they are said to be “pissing in high cotton.”

Floyd is 84 now, and desperate to finish writing down his life story. He sees it as his life’s last goal he hasn’t accomplished. He refers to the project as a closing of his life’s circle. I’m not sure if he invented this term. It doesn’t feel like a Floyd original.

He’s been jazzed, these past couple weeks, on something Harriet said to him a few years ago. During an interview session, she asked him, “When was it that you realized you were extraordinary?”

Floyd keeps bringing this up - Harriet’s comment seems for him as life-giving as his a.m. Vitamix smoothie, his daily exercise, his writing. He will retell it, and then he’ll say, “I didn’t know I was extraordinary,” trying to make himself sound demure and modest when in fact Harriet’s choice word confirms suspicions he already had about himself. It’s not surprising he’s fashioning it into a kind of mantra.

But it’s true: as time passes, there are fewer and fewer people like Floyd.

Help support our creative team –become a member of our Readers’ Circle now!