French Market Memories: My Last Sip at Morning Call

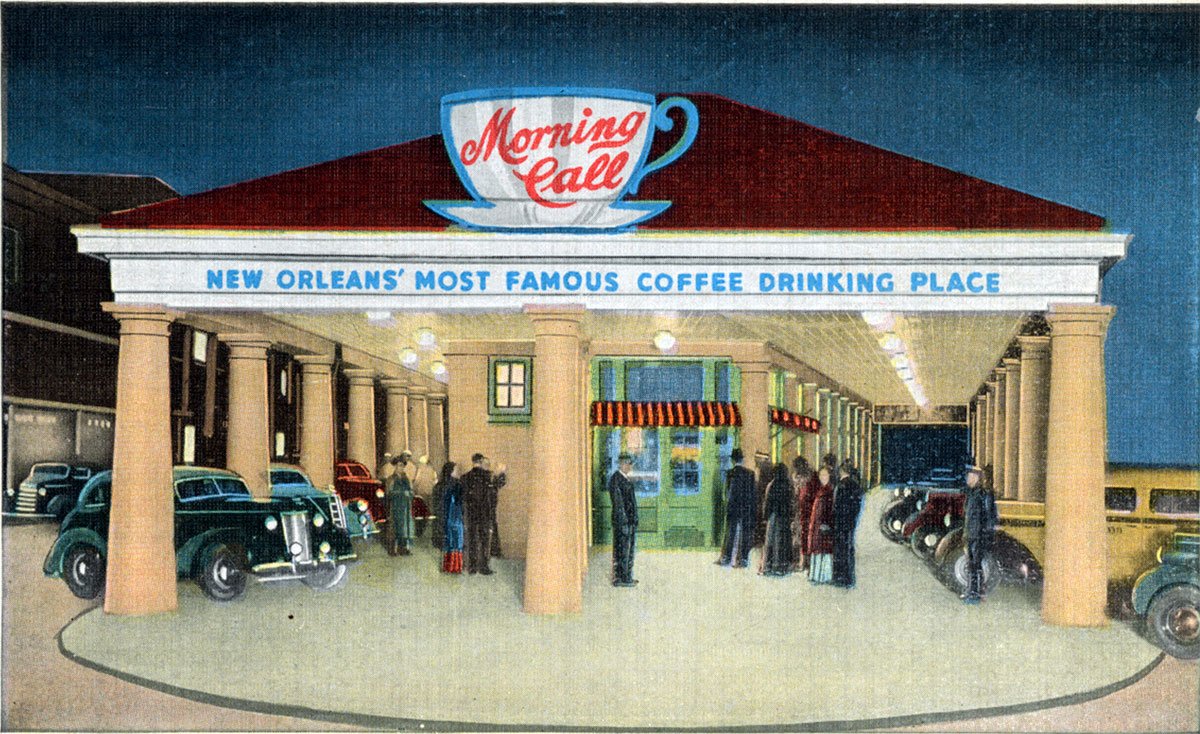

Postcard by E. C. Kropp Company, 1934 - 1944, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

February 2024On the eve of Morning Call’s closing fifty years ago, a young writer joins a crowd of locals lining up to pay their respects - and savor one final cup of coffee.

– by Bethany Ewald Bultman

As the last call loomed at Morning Call in the French Market on a February Thursday in 1974, the glacial mist blowing off the river didn’t deter those of us who had come for one final cup of coffee. The closing of the century-old coffee stand in the French Market brought many of us out into the brutal cold to mourn, waiting, three and four deep.

The day before (February 27 – Ash Wednesday), New Orleans’ temperature had dipped to that year’s low of 24 degrees. The weather reflected the mood of those who assembled, as did the empty French Market, the rest of it gutted and undergoing the early stages of transformation – from thriving historic produce market to tourist destination. In the dark frigid night, Morning Call was the only remaining island of golden light and warmth.

At the time, I was a Tulane student and working a few blocks away at the Vieux Carré Courier, on Decatur Street. A few of the women from the office and I had dressed in widows’ weeds – black dresses, ratty Persian lamb coats and hats we’d scrounged from thrift shops – to mark the closing of our favorite “office escape” hideaway.

Our attire seemed apt as we passed by a makeshift coffin labeled “Al and Eddie’s Last Call for the Morning Call.” The two current owners were brothers Al and Edmond Jurisich, descendants of the founder, Joe Jurisich, Sr., who established the coffee stand in 1870. In the late 1800s, Morning Call was one of 500-plus coffee houses in New Orleans.

French Market 1880 -1897 by William Henry Jackson, Library of Congress

Morning Call in the French Market by Stephen Duplantier, circa 1889 - 1913, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection

Ironically, Prohibition transformed late-night coffee drinking in the French Market into a tradition beloved by New Orleans’ cafe society, students, and artists. In January 1920, the 18th Amendment went into effect, prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States. At the time, New Orleans boasted of having more than 5000 bars, many of which were in the French Quarter. As the city’s longest-serving mayor (1904-1920) Martin Behrmann (1864-1926) boldly asserted, “You can make it illegal; you can’t make it unpopular.”

By the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, New Orleans society had adopted the French Quarter as their mecca for the syncopation of Jazz and the buzz of illegal gin. A jolt of java at the Morning Call became integral to every excursion to the French Quarter.

Traditionally, from 7pm to 11pm, the Morning Call’s patrons – both inside and for automobile-side service – were mainly French Quarter families with children. By 11pm, the society folks began dropping in after plays at Le Petit Theatre (near Jackson Square), or concerts or balls in the new Municipal Auditorium, which opened in 1930.

After midnight until 3am, musicians and those who had been enjoying Bourbon Street would take over the stools. Before dawn, artists and writers joined the late-night coffee drinkers until the truck gardeners came in after unloading their produce. By 8am, office workers filled the stools.

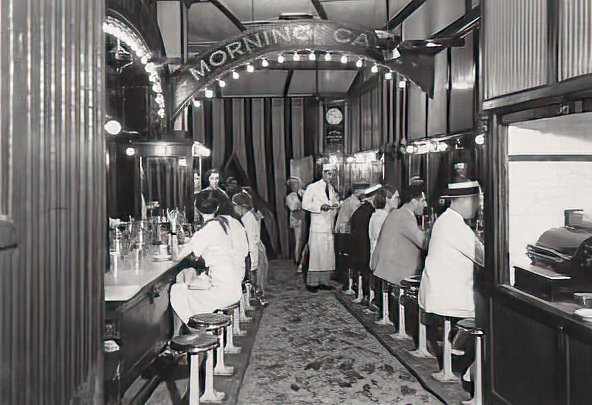

Interior of Morning Call between 1934 and 1939, by unnamed WPA photographer.

According to a 1928 article in the Times-Picayune by James Sibley, Morning Call was the “no class distinction destination for everyone from sweet young debutants to unshaven hucksters.”

Sibley reported that the French Market coffee stand was selling 1500 cups of coffee and 20,000 donuts daily that year. The inside waiters were paid $3 and the outside car hops earned $2 per day. They made far more than that in tips, so jobs at the coffee stand were very sought after.

I first visited Morning Call nearly thirty years after Sibley’s article, in the summer of 1955. For my sixth birthday, my parents let me spend a week with my New Orleans cousins. One night, bundled in our pajamas, we kids were piled into the back of their massive family Buick. Once in the French Market, pillows of fried dough dusted with powdered sugar were served to us by the car-hop waiters in their starched white jackets and paper hats.

Café au Lait Junior tasted like pure heaven: hot milk flavored with a splash of coffee and chicory, and so much sugar that the spoon almost stood up by itself. How mature we felt, drinking out of heavy white mugs delivered on a tray attached to the car window. That night, I began dreaming of living in New Orleans as a grown-up, so I could bring my future children to enjoy this ritual.

A 1950s postcard of Morning Call, courtesy of The City Archives & Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library

By 1970, as a Tulane student working part-time at the Vieux Carré Courier with its office in the 1200 block of Decatur Street, I was a frequent visitor to both the French Market and Morning Call. Writing a paper for my sociology class on French Market workers gave me the opportunity to meet one of the donut makers. While I don’t recall his name now, my visit into that kitchen is a crystalized memory.

The burly day-shift baker had worked at Morning Call his whole life, having inherited his role from a relative. For a small man, he had superhuman strength to hoist the massive bags of flour. I recall he told me, “No shortening, young lady. That’s why our donuts melt in your mouth and are easy to digest.”

His donut-making (he never called them beignets) proficiency had all the showmanship of a sleight-of-hand trick. He claimed that he mixed his batter by hand faster than any mixer. In the blink of an eye, he’d rolled the dough out wafer thin and had sliced it into rectangles with a dull kitchen knife. Before I knew it, he was hurling the slices of dough into a cauldron filled with eight gallons of sizzling fat. Viola! Two minutes later, he pulled out the puffy golden treats.

Morning Call’s coffee and chicory, dripped in five-gallon batches several times an hour, possessed its own alchemy. Their coffee urns, forged of Monel metal (nickel and copper with small amounts of iron) were the invention of Mr. Joe, Sr. to ensure resistance to corrosion from the acids in the coffee and to rust. They were tapered at the bottom, with long spouts and hefty handles.

The waiters simultaneously poured a pot of hot milk with one hand and thick, syrupy coffee with the other. By artfully pouring it into the cups, the perfect cup of frothy café au lait resulted. (The trick I learned was that “patrons in the know” requested “pure heated skimmed cream” instead of milk.)

Morning Call Waiter, 1935, by Charles L. Franck, courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collections

Pepe Citron, The States-Item’s intrepid “Lagniappe” editor, sounded the alarm about Morning Call’s closing in his column the Saturday before Mardi Gras, February 23, 1974. After more than a hundred years in the French Market, the city’s revitalization plans were forcing Morning Call to move. The Jurisich brothers had found another location in “Fat City,” a new entertainment strip in nearby Metairie where muggings were unheard of, rents were cheap, and parking was ample.

Citron wrote, “How many hundreds of mornings did we… my girlfriend (now wife) and friends, enjoy the Quarter nightlife and the walk (skip) through the streets in the hopes to relax over coffee and donuts [at Morning Call]?

“It was a tradition generations old… a good tradition, where bankers, businessmen, tradesmen, whores, musicians and tourists rubbed elbows and spilled powdered sugar (from chained mugs) over each other.”

Citron had eloquently concluded in his column: “Progress, it seems, must hurt the one it loves… the historic areas and institutions which it allegedly is attempting to save.”

By the time of Morning Call’s last evening – just two nights after Mardi Gras 1974 – it was the last business operating amidst the rubble of the reconstruction in the lower French Market, work that had begun in 1971. Its lights were the portal into the darkness beyond, where rows of stately columns from the historic produce market stood out like dystopian remnants of an abandoned movie set.

A section of the original French Market in 1937, showing major deterioration. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston, Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Read about Frances Benjamin Johnson in this FQJ story by Frank Perez.

The wait was long, but the crowd parted to allow the passage of Bourbon Street club owner and exotic dancer, Chris Owens (1932-2022), and her handsome male escort with his blond pompadour. By the time I got inside, their matching floor-length white mink coats puddled over the seats of the hard wooden stools onto the meticulously scrubbed floor. With their elbows on the marble counter, they were just there like everyone else, to indulge in the ritual of the Morning Calls’ coffee and donuts one final time.

To this day, I carry a profound sense of comfort from that special night – the combination of the bright bulbs, the unique, nutty aroma of the special coffee roast, and the intimacy of sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with other New Orleanians on a bitterly cold night.

And just like that, it was over.

We were savoring our last sips of coffee when the lights were blinked on and off. It was almost midnight. My black clothing and that of my friends was dusted with sugar, a cherished souvenir of our repast. Off into the brisk night we went, back to our diverse lives, enriched by a memory.

I heard later that customers who were more reluctant to give up their stools sang Auld Lang Syne, but when we left, the kitchen was being scrubbed as its own act of closure and the wizened faces of the waiters bore no more welcome. They were ready for the next chapter to begin in Fat City.

In the obituary the Vieux Carré Courier ran for the French Market centenarian in advance of the coffee shop’s move to the suburbs as “yet another example of the piecemeal erosion of the city’s soul, its distinctive sense of identity and place. Like so many other local institutions, Morning Call is now to be supplanted by… well, the reigning word seems to be Progress. We’re not anti-progress, we’re simply pro-Morning Call – and pro-French Quarter and pro-New Orleans.

And by any civilized New Orleans standard, this is a damnable outrage.”

Morning Call obit from the Feb. 7, 1974 issue of the Vieux Carré Courier, courtesy Steve May and THNOC

Your donations make stories like this one possible: