New Orleans Italian Boxing Champions: Forged Out of Tragedy

March 14, 1891, photograph of the crowd in the Parish Prison yard during one of the worst mass lynchings in American history, THNOC, 1981.328.33

February 2025Part One of Four

The 1891 lynching of eleven Italian Americans later motivated generations of young men who punched their way past discrimination in the early 1900s.

– by Bethany Ewald Bultman

In the 1920s, middle-weight boxer Jimmy King, whose family name was Anselmo, was a top contender. Photo courtesy Jimmy Anselmo

Jimmy King’s Mardi Gras Club on Bourbon Street, date unknown, photo courtesy the Vieux Carre Commission Library. King bought the building in 1946.

In early 20th century, Bourbon Street’s 300 block had a king: Former regional welterweight champion Jimmy King. Born in 1903 in his family’s grocery, he knew that his Italian heritage carried a heavy legacy. He boxed his way out of the stigma.

After hanging up his gloves, King owned a handful of successful clubs and restaurants near the intersection of Bourbon and Conti Streets, a section lined with the businesses of an elite group of Sicilian boxing promoters and former fighters – like Diamond Jim Moran ( born Broccato) and Pete Herman (born Gulotta).

King, nicknamed“Kong” by his buddies, opened his first club in 1946. His son had been born a few years earlier, in 1944, and the boxer was proud for the child to carry his Italian family name - Anselmo.

The younger Jimmy learned the ropes of owning a club by noodling around on the drum kit before opening hours at his father’s Mardi Gras Lounge. The Quarter was a close-knit community, giving the child a sense of security. Everybody looked out for one another.

Jimmy Anselmo in front of Jimmy King’s Mardi Gras Club at 333 Bourbon Street, circa 1949, photo courtesy Jimmy Anselmo

Jimmy Anselmo in front of 333 Bourbon Street in January 2025, photo by Ellis Anderson

Anselmo says he was schooled about his father’s impressive boxing career from Frank Sinatra.

As he recalls, his dad met him after school at McDonough 15 on St. Philip Street. From there, the middle schooler and Jimmy King walked over to The Dream Room at 426 Bourbon.

“Frank Sinatra was sitting there alone in a closed club waiting to meet my dad,” recalls Jimmy, with a note of lingering disbelief. The rest of the afternoon, Sinatra, a boxing aficionado, peppered Jimmy King with questions about his legendary bouts fought twenty years before.

Jimmy Anselmo, points out the place where he and his father met with Frank Sinatra. January 2025, by Ellis Anderson

It turned out that King had something in common with Sinatra’s dad. Sinatra had been born in 1915 to Italian immigrants in a Hoboken, New Jersey tenement. His father, Martino Sinatra, was an illiterate bantam-weight boxer whose ring name had been Marty O’Brien.

To get ahead, both King and O’Brien disguised their Italian heritage because of discrimination. The national prejudice against Italians reached its height in 1891, brought on by an atrocity committed a few blocks from Bourbon Street.

***

Richard Gambino in his 1977 book, Vendetta: A True Story of the Worst Lynching in America, described the lingering repercussions from this New Orleans tragedy that impacted the Italian immigrant population all across America.

After the unsolved 1890 murder of the Irish police chief, David Hennessy, more than two dozen were arrested. New York’s L’Eco D’Italia had notified Italians on the East Coast of ongoing persecution in New Orleans. By amassing small donations, the defendants had a war chest of more than $75,000.

It wasn’t enough, though. In March 1891, rough justice in New Orleans trumped the American legal system, and eleven Italian men - some who had just been declared innocent by a jury – were lynched.

The Police Chief’s Assassination: 1890

The torrential rains had subsided as the 32-year-old police chief, David Hennessy, traversed streets seething with mud and deep puddles.

He and his buddy, Captain Billy O’Connor, had stopped off to eat oysters en route from the French Quarter police headquarters to the home he shared with his widowed mother on Girod Street (Loyola Avenue today, near Superdome).

275 Girod Street, Hennessy's home, Historic New Orlean Collection, 1974.25.25.215

As Joseph E. Persico described, when the pair got near Hennessy’s home after 11pm, “the chief told O’Connor it was not necessary to accompany him any further.”

David Hennessy, courtesy Tulane University Special Collections

Had the chief, with many death threats hanging over him, forgotten them for the moment? Had it slipped his mind that he was involved in a major prosecution? Or perhaps he didn’t remember it was the tenth anniversary of the day he’d killed a fellow police officer.

In October 1880, Hennessy had shot Thomas Devereaux – his rival for the position of Chief of Police – in the back of the head inside a Gravier Street business. While he was acquitted of the murder and fired from the police department, it did nothing to appease Devereaux’s allies.

Later, Hennessy was rehired and elevated to head of the department by Mayor Joseph Shakespeare. Shakespeare had been born in New Orleans to Swiss-German Quaker parents. The Mayor’s “Shakspeare Plan” involved regulation and revenue collection of the city’s thriving (and illegal) vice trade. Chief Hennessy’s vehement unpopularity with many current and former policemen made him a controversial choice to lead the force.

Chief Hennessy was tasked with the consolidation of the police force and tax collection to make sure the Ring, the corrupt old-guard that ran the city, was cut out. Under the Ring, brothel and gambling operators paid protection money to policemen. At the time, policemen earned very little, out of which they had to buy their own uniforms and whistles. Most of them viewed bribery, extortion and protection rackets as the perks of the job. With the new chief enforcing Shakespear’s plan, that source of income was threatened.

In addition, many of Devereaux’s colleagues from his days in the state legislature and as the Chief of Detectives for the New Orleans Police Department had vowed revenge against Hennessy.

“Scene of the Assassination” in The Mascot newspaper, New Orleans, 1890, Creative Commons

Chief Hennessy stood alone on the dark street when the shots rang out, because the police officer who was supposed to be on guard at the chief’s residence was not there.

Persico recounted the details of the assassination that would launch the horrific lynching.

On that hazy night in 1890:

Captain O’Connor heard the gunfire, rushed to the scene, and found Hennessy on Basin Street, where he collapsed after gamely pursuing his assailants.

“Who gave it to you, Dave?’ O’Connor asked.

“The Dagoes did it.” Hennessy murmured.

Hennessy, lucid for most of the time before he died, expired ten hours after he was shot. Although he had ample opportunity, he never described his killers to any of his visitors at Charity Hospital.

Follow the Money

Hennessy’s demise was music to the ears for several groups, but as if snapping a wishbone, Mayor Shakespeare grabbed the “dago” option with both hands. In that one snap, he unified all of his rivals against a common enemy: The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Local, national and international press gobbled up Mayor Shakespeare’s Italiaphobic nativist narrative which claimed “New Orleans was the haven to the worst classes of Europe: Southern Italians and Sicilians.” He characterized the city’s immigrants as "filthy in their persons and homes, without courage, honor, truth, pride, religion, or any quality that goes to make a good citizen."

At the time, New Orleans was the tenth largest city in America, with a population of 250,000. Across Canal Street from Hennessy’s final stroll that October night, more than 30,000 Italians were crammed into a half-square mile inside the French Quarter and the adjacent Tremé.

This was a self-contained immigrant community that produced, sold and exported food – from farms and fishing boats to corner stores to the docks. By 1890, Italian immigrants owned more than 3000 businesses in New Orleans. With eight thousand registered voters, the Italian- American political and economic power was beginning to threaten New Orleans’ old guard.

Within hours of Hennessy’s death, the local Picayune (newspaper) reported that the mayor ordered the police to "arrest every Italian you come across (in the vicinity of Hennessy’s residence)." Within three hours, five dozen Italian men had been booked for the murder. By October 22, every cell in the French Quarter’s Central Police station was bursting at the seams with Italians.

Mayor Joseph A. Shakespeare, Wikipedia

Meanwhile, the Mayor had appointed a “Committee of Fifty” as combination prosecutors-propagandists, funded by the New Orleans City Council. The Committee saw to it that the chief’s brazen murder was on the lips of locals and visitors as thousands lined up to gaze at Hennessy’s corpse lying in state in City Hall (Gallier Hall today). They afforded Hennessy the same level of pomp that the funeral of former Confederate President, Jefferson Davis received the year before, in December 1889.

One of the 250 Italians arrested was Joseph P. Macheca, a produce kingpin, one of the wealthiest men in the state and a former delegate to Louisiana’s Democratic convention. He’d revolutionized the international fruit import business, distributing tropical fruits from Central and South America all over North America.

Macheca, his Irish wife, the former Miss Bridget O’Dowd, and their eight children were respected citizens. The fact that Macheca fleet’s lucrative ten-year dock contract would expire in 1892, made his implication in Hennessy’s murder a viable way the Committee of Fifty could nullify his influence.

In a portrayal worthy of HBO’s mobster, Tony Soprano, the Committee cast Macheca, a forty-seven-year-old businessman as “the prime architect of Hennessy’s assassination.”

As the trial began nearly four months later, in mid-February 1891, the last thing that the Committee of Fifty wanted to have investigated. Historians speculate now that some of the most vocal anti-Italians in the group, may have been the ones who orchestrated Hennessy’s murder.

In the end, nineteen of the Italian prisoners were indicted and nine of them were tried.

There was not one credible witness to the murder. In Gambino’s book, Vendetta, he reveals that to ensure the Italians were convicted, the Committee of Fifty funded one Pinkerton detective to infiltrate the defense team and another to pose as a prisoner to get details of the “crime.”

Governor Francis T. Nicholls, Wikipedia

They also churned out propaganda about bribed jurors. As Proseco sums up in his 1973 American Heritage article, “Almost from the outset of the trial an undercurrent of insinuation and suspicion had swirled around the integrity of the jury.”

One of the defense attorneys, the illustrious Lionel Adams, was known nationally as “the brilliant beardless lawyer from the South.” His knack was jury selection. For this trial, he interviewed more than seven hundred men before seating an impartial twelve-man jury. They listened to more than a hundred witnesses provide flimsy circumstantial evidence.

By Friday, the thirteenth of March, spectators had grown restless. The jury had been out since the previous evening. At 2:53pm the jury came back with their verdict. Not one of the defendants was found guilty.

The New York Times reporter recounted in the front page story, “So strong a case has been made by the State, the evidence has been so clear, direct and unchallenged that the acquittal of the accused today came like a thunder-clap.”

After the verdict was read, the Italian community let out a collective sigh of relief. Soon jubilation erupted on the levee in Luggar Bay, near the French Market, where the Macheca fleet was docked. “[The Italian boat owners] hoisted two flags on their masts - the Italian flag above, the Stars and Stripes below, upside down,” noted Joseph Persico in his article.

However, no one walked free that day. The vindicated defendants were transported back to Orleans Parish Prison in case future indictments would be forthcoming.

In response to the verdict, a Vigilance Committee of sixty-one prominent men gathered to formulate a call to action. The following morning, the local papers ran their invitation to citizens to “come prepared” to take the appropriate extrajudicial course of action to rectify the verdict of the “corrupt” judge and jury. Their invitation to do harm to the vindicated Italians spread as quickly as cholera.

Excerpt from the evening edition of the Times-Democrat, March 14, 1891

Excerpt from the evening edition of the Times-Democrat, March 14, 1891

Louisiana governor, Francis T. Nicholls (1834-1912, governor 1888-92) declined to intervene to protect the innocent men without a special request from New Orleans’ mayor. Nicholls clearly didn’t want to ruffle any feather of the city’s power elite.

That morning the mayor was unreachable. It was later learned that he had retreated to the stately Pickwick Club (corner of Carondelet and Canal) to eat his breakfast without disruption.

The Henry Clay statue was a local landmark from which many Carnival parades and processions set off their celebrations. Circa 1880s - ‘90s, Library of Congress

9:45am, Saturday, March 14

More than five thousand men of varying social casts, religions and ethnicities assembled at the intersection of Canal and Royal Streets, surrounding the statue of Henry Clay, the late Kentucky Senator and war hawk.

Citizens Mass Meeting at the Clay Statue, Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.25.226

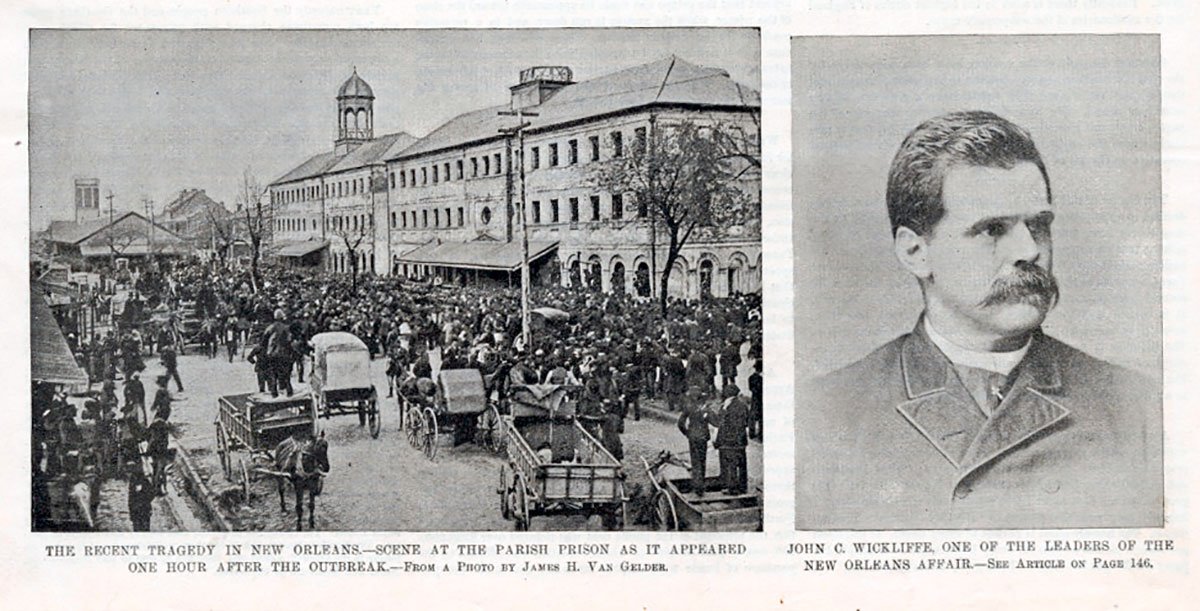

The Recent Tragedy In New Orleans, The Popular Gathering At The Clay Statue Preparatory To the Attack On The Parish Prison, Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.199 i,ii

Promptly at 10am, New Orleans attorney William Stirling Parkerson (later, president of the Louisiana Bar Association) exhorted the assembly to "set aside the verdict of that infamous jury, every one of whom is a perjurer and a scoundrel.”

Within half an hour, the multitude was shouting in unison: "We want the dagoes!"

The advancing mob was led by Parkerson and other civic leaders, including John C. Wickliffe, editor of the New Delta newspaper; John M. Parker ( later Louisiana’s Governor,) and Walter C. Flower (a future New Orleans’ mayor). They marched up Royal to Bienville where a fifty-man “assassination squad” called The Regulators – led by First Lieutenant Major James D. Houston – was waiting to join them. Their Winchester rifles, paid for by $15,000 given to the Committee of Fifty by the New Orleans City Council, were slung over their shoulders.

photograph of the crowd moving toward Parish Prison, HNOC, 1974.25.3.255

As Joseph Persico related, “The crowd, now swollen to well over six thousand and whipped into a righteous fury,” headed to Parish Prison on Rampart (site of the Municipal Auditorium today).

The warden had already left the prison for the day, despite having read the day’s paper inciting citizens to storm his facility. His second in command transferred the Italian prisoners to the women’s section. Two Italian prisoners must have “smelled a rat” because they crammed themselves into the warden’s bull terrier, Queen’s, doghouse.

The prison, more than a half-century old, was located several blocks away (near the present-day site of the Municipal Auditorium in Armstrong Park). During the day, prisoners were herded into segregated courtyards. At night, thousands of them fought for space on the bare floor of the dilapidated prison building. THNOC, 1974.25.3.254

10:30am, March 14, 1891

The chanting horde advanced on the prison and the killings were carried out with rapid, ruthless precession by The Regulators, a disciplined "execution squad" of several dozen men.

11am - Eleven Dead

Twenty minutes after the prison’s Treme Street door was battered open, the murderous mission was accomplished. Eleven men lay dead. Five of these had never been tried. Three had been acquitted. The other three had their charges dismissed. (Eight more prisoners evaded the assassination squad).

Newspaper sheet with illustrations and articles relating to New Orleans, Historic New Orleans Collection, 1989.91.43

The jubilant crowd lifted Parkerson on their shoulders to return to the Clay statue, where the way was lined with people cheering from their balconies. Back at the prison, some of the assassins were showing off their handiwork to the press.

Outside, bystanders cheered as the mutilated bodies were displayed. One of these, James Caruso, had been shot more than forty times. Some corpses were hung; others ripped apart as their bodies were plundered for souvenirs. Women cheered the men on, some mopping up the blood with their handkerchiefs to save as trophies.

The Pittsburg Dispatch of March 15, 1891 described the scene in New Orleans at 12:30pm when Coroner Lemonnier broke up the mob. By that time, the tree where Bagnetto hung had nearly been chopped down for gruesome mementos. The police cut down two strangled bodies swinging from lamp posts. They discovered more bodies, gunned down execution style, stretched side by side in the prison yard.

1942 drawing “The Lynching of the Italians” by John McCrady, THNOC, 1988.97

Monday, March 16, Gone But Not Forgotten

On Monday, March 16, a reporter from The Daily City Item was on hand at the Macheca home in the 1200 block of Bourbon. It was noted that the victim’s face bore the agony of his last moments as he lay in the stately casket adorned with gold and silver. The Orleans Parish coroner’s report confirmed that Macheca had been clubbed to death with the butt ends of rifles and pistols.

That same day, twenty-five carriages followed Macheca’s hearse in the solemn cortege to his funeral mass at St. Louis Cathedral. The route was lined with solemn mourners. Most of the black-clad women clutched flowers as Macheca’s six adult children and their families passed.

Macheca’s six pallbearers, the papers noted, were not Italian. His final resting place in St. Louis No. 3. (3421 Esplanade Avenue)

Six weeks after his death, the dock contract was awarded to Major Houston, who had led the squad of assassins.

Nation Press Applauds New Orleans for Big Stick Justice

These were not killings hidden in the dark of night. These were respectable citizens righting a “wrong” with ladies present.

On March 16, The Boston Globe front-page headline exalted, "STILETTO RULE: New Orleans Arose to Meet the Curse."

The March 15, 1891 New York Times front page headline extolled, “Chief Hennessy Avenged...Italian Murderers Shot Down." The names of the vigilante leaders were proudly listed in the two columns given to applaud their “noble” actions.

0n March 21, 1891, the soon to become the 26th US President, Theodore Roosevelt wrote to his socialite sister-in-law, Anna, (mother of Eleanor Roosevelt), describing dining with “various dago diplomats.” Roosevelt noted that they were “wrought up by the lynching of Italians in New Orleans.” To which Roosevelt stated, “Personally, I think it rather a good thing and said so.”

In the Aftermath

Three of those lynched in 1891 were Italian citizens. The Italian government demanded that the US government bring the leaders of the mob to justice. When nothing was done, diplomatic relations were severed. In 1892, fearing war, seizures of American ships, or a blockade of the Mississippi River, U S President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901, President 1889-93), declared a national holiday on Columbus Day to soothe the Italian Government. The US government paid $2,211.90 in reparations to each victim’s family.

Hennessy’s tomb in Metairie Cemetery, photo by Sally Asher

In 1893, Gaspare Marchesi, the boy accused of having blown a whistle to alert the assassins of Hennessey’s approach, and survived the 1891 attack by hiding in the prison while his father was lynched, was awarded $5,000 in damages after successfully suing the city of New Orleans.

The city spent far more erecting a 26-foot police baton, worthy of Freud, to commemorate the slain Police Chief than it did compensating the victims of the carnage.

On Friday, April 12th, 2019 the City of New Orleans and Mayor LaToya Cantrell issued an apology for the lynching of 11 Italian immigrants. A commemorative plaque is located behind the Municipal Auditorium in Armstrong Park.

***

Jimmy Anselmo grew up in the Tremé and the French Quarter neighborhoods. Although the Quarter was “mostly owned by Italians then,” and the community was very close-knit, he doesn’t remember hearing about the lynching. He only learned about it when he was older.

“Of course, it wasn’t taught in school - there were lots of things we didn’t learn back then,” he said. “We weren’t taught anything about the Trail of Tears either.”

But lessons of tolerance and acceptance still filtered down in the Italian community. Anselmo recalls there always being a good bond between Blacks and Italians. He played with Black kids growing up and his father featured Black musicians like George Lewis and Dave Bartholomew in his clubs.

His dad, Jimmy King, who grew up in the shadow of the 1891 lynching and faced open discrimination, told him from an early age, “Son, we can’t change the way we were born. Treat everyone with respect.”

Next month: Part 2 of the Boxing Series:

The French Quarter Kings of Boxing and Bourbon Street

For a full bibliography of sources used in this article, open this .doc file.

Your support makes stories like this one possible –please join our Readers’ Circle today!